May 21st, 2021

Closing the Gap Between Dreams and Reality: On the Work of Ta-Nia

By CAITLYN TELLA

Caitlyn and theater-making duo Ta-Nia discuss embodiment, multimodality, and afrofuturism.

Dreams in Black Major at NYU Tisch / National Black Theatre. Photo Jeff Lawless.

Dreams in Black Major at NYU Tisch / National Black Theatre. Photo Jeff Lawless.Dr. Barbara Ann Teer, the late, visionary founder of Harlem’s National Black Theatre, was committed to art that “emanates from an African world-view and is grounded in spiritual tradition,” a standard, she wrote, that inherently “removes the separation between audience and stage.” Ta-Nia, a theater-making duo in Brooklyn, whose formative collaboration, Dreams in Black Major, premiered at the National Black Theatre in 2019, excavate that separation in their practice-based research. If the proverbial stage entertains limitless fantasy and the audience sits in concrete reality, what lies between? Ta-Nia intricately perceive the possibilities of that synthesis to build a new space. In their words, “a blk space in an anti-blk society.”

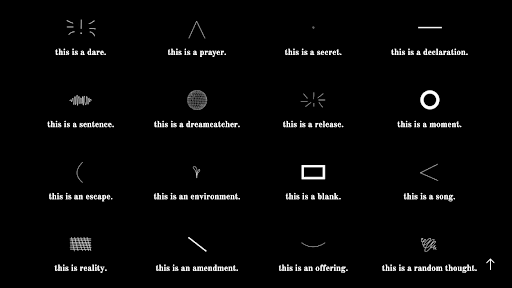

To understand what I mean when I say that Ta-Nia intricately perceive the liminal, participate in The Map Project. It’s a digital tour through the capacity of your own imagination to envision utopia, guided by meditations, video art, and dozens of prompts written by Ta-Nia. It works by initiating participants into the wisdom tradition of their own sensory faculties and applying that wisdom to realize the Afro-future. Ta-Nia crafted the experience to collect written material for A Map to Nowhere (things are), a performance/ritual in development through Soho Rep’s Writer/Director Lab. Since August 2020, over 150 people have participated, with over 500 responses recorded. “We find it crucial for our projects to contain the DNA of our community,” they say.

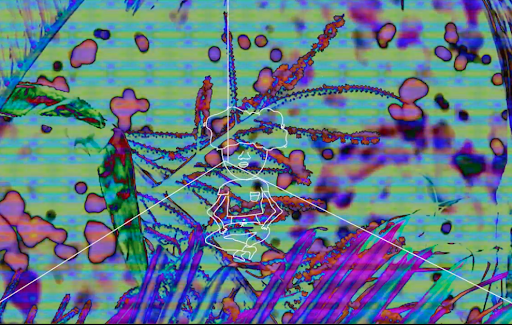

Screenshots from The Map Project. Website designed by Talía Paulette Oliveras.

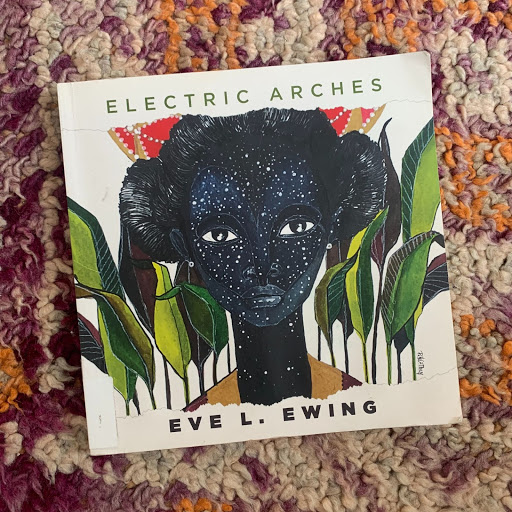

In Electric Arches by Eve L. Ewing, a poetry book that inspired A Map to Nowhere (things are), “The Device” tells the story of a new technology invented by “a hive mind of Black nerds” to communicate with and receive guidance from ancestors. Imagine the device through the aesthetic lens of Afrofuturism and you might picture a metallic, sleek, cosmic gadget. As it turns out, the device is “an inelegant hodgepodge, a reflection of the hands that made it.” One scientist's reflection: “It looked like in a hundred years it might be something you’d find at a yardsale. But of course...wouldn’t that be a success? Shouldn’t the device come to be so average and commonplace that it ceases to be magic and comes to be part of everyday life for regular black people all over the country?” This question expresses Mundane Afrofuturism, a tenet of Ta-Nia’s project.

Elucidated in Martine Syms’ manifesto, Mundane Afrofuturism is a framework for cultural production that combines the vision of Afrofuturism—–Black liberation–—with a critique of its spiritual bypasses. It applies the laws of physics (gravity) to Afrofuturism, and in doing so, roots the radical Black imagination on earth. “Outer space will not save us from injustice,” writes Syms, and “the most likely future is one in which we only have ourselves and this planet.” Sprawling mycelium networks, with their ancient abilities to nourish entire ecosystems and detoxify the environment, are, after all, mundane by definition. The Map Project and its spawn, A Map to Nowhere (things are), embody this type of technology to world-build.

Nia Farrell and Talía Paulette Oliveras, photo Bianca Rogoff

In early spring I corresponded with Ta-Nia on a shared doc about these influences over the course of several weeks. While they mainly wrote as a singular entity, they are, by the way, Talía Paulette Oliveras and Nia Farrell. “Nia,” writes Talía, “is a master of puns and poetics, a supernova gracing us with its brightness, an infectious joy embodied.” While “Talía,” writes Nia, “is the manifestation of dreams and a catalyst for the possibilities of this world, with a rose in one hand and a machete in the other.” Together, they alchemize a way of working and being otherwise inaccessible.

︎

Video stills from The Map Project designed by Ava Elizabeth Novak, concept by Ta-Nia.

CAITLYN

Can you talk a bit about how you’re translating The Map Project responses from the virtual realm to the performance of A Map to Nowhere (things are)?

TA-NIA

We worked with two incredible archivists, Jordan Powell and Nina Attinello, who helped us sort through all the website submissions and track recurring themes, repeated dreams, and striking imagery.

With those 50-something Google doc pages of responses, we’ll identify the quotes and visual language that we want to incorporate directly in the script. Sometimes we’ll put responses in conversation with one another by creating a poem of different dreams for a character to perform. And other times, the submissions, individually and collectively, influence the physical environment. Colors, sounds, and textures that people included in their dreams may find their way into our collective theatrical space. One of our hopes as creators is that a person who participated in The Map Project walks into the space and sees or experiences their dreams actualized.

CAITLYN

“I wanted a map / not to know / where things are / but to know / where I am” appears in all caps in Eve L. Ewing’s book, Electric Arches. This also reflects the title of your show. Ewing’s poetry takes many forms, including sestina, narrative prose, epistolary, five-act structure, and the “re-tellings” where she uses her own handwriting to redirect and transmute a traumatic narrative. Her writing also continually insists on joy and meaning, not as divine privileges or future states to inhabit, but as the basis of her own perceptions, all in the context of the status quo of anti-Black violence. There’s a lot more to say about it. How does this particular book influence your piece?

TA-NIA

You identified many of the reasons we fell in love with Eve L. Ewing’s writing and this collection of poems in particular. As our project evolved from an adaptation of the book to a conversation with the book to a piece that is inspired by the book, there are two elements of Ewing’s that we’ve clung to.

First, the re-tellings. The act of re-telling and transforming an inherited or lived narrative is a powerful one. These re-telling poems remind the reader of their agency and imagination—two essential components for future-building. In the way Ewing activated us as creators to re-tell our stories, we want to activate our characters and audience to do the same.

The other element of Ewing’s work that serves as an emotional undercurrent for our characters and the structure of the piece is her core question in “The Device,”––how can we as Black people be free in a world that does not love us? At its core, A Map To Nowhere (things are) is a ritual for the audience to ask and answer that question for themselves.

CAITLYN

Martine Syms writes that Mundane Afrofuturism recognizes “the sense that the rituals and inconsistencies of daily life are compelling, dynamic, and utterly strange.” How does this inform the work you do as theater-makers to “make blk spaces in an anti-blk society”?

NIA

I’m excited for what Talía thinks about this question! The way I understand this quote and its relationship to our work is that, in isolation, concepts of actualization and manifestation might appear to be nonsense. But I think rituals are only “utterly strange” if they don’t lead us to action. Dreams of liberation that only remain in the head, now that’s strange to me! But dreams that become a blueprint for the future we will coexist in, now that’s just practical. My Afro-future isn’t going to drop out of the sky, it must be rooted in deliberate and intentional acts of community building.

TALÍA

A big part of making blk spaces for me has to do with recognizing the ways blkness is inherently complex, multiple, dynamic, ephemeral, transformative and so on. The rituals and inconsistencies of daily life that Syms refers to feel intrinsic and synonymous to blkness—it almost makes me think that, in our work, the first step to making our spaces blk is by leaning into the mundane.

Video stills from The Map Project designed by Ava Elizabeth Novak, concept by Ta-Nia.

CAITLYN

Syms also writes “to burn this manifesto as soon as it gets boring.” What is your relationship to building upon the legacy of your mentors and predecessors while remaining true to your aims?

TA-NIA

We thank and honor the ancestors and community leaders and mentors who have guided us to this point. It is because of their work we stand on a solid foundation that we aim to only add to—whether that be continuing the work or finding new ways that lead us to the ultimate goal: the liberation of Blk people.

We love that last line of the manifesto; it keeps us accountable to our people who we wish to service. We like to think of burning not as destroying, but an act of creating something new. The volcano erupts to make an island. The fire rages to release seeds and forge a new path. We hope that when the flames come for our work, it follows in that tradition of burning in order to see what other form exists on the other side.

And if our rituals no longer respond to the needs of the community, or worse, work in antithesis to the needs of the community, for sure burn it down! We hope that the future ancestors rise from the ashes anew.

CAITLYN

How did working at the National Black Theatre influence your approach to producing theater?

TA-NIA

A shout out to the folks at National Black Theatre (NBT) who supported Dreams in Black Major: Sade Lythcott, Jonathan McCrory, Nabii Faison, Abisola Faison, Denzel Faison, Belynda Hardin, and Kiele Logan and the entire facilities team—we are in deep gratitude for the space you made for us to actualize our dreams. We hope we made Dr. Barbara Ann Teer proud.

The energy of NBT fundamentally changed our piece. We didn’t have to carry the baggage of our work in a traditionally white theatre institution. No, we walked into a Blk space and immediately felt closer to our dreams. There’s a reason why NBT is called “your home away from home.” It’s where Blk artists undergo a soul journey to tap into the soul of what we do and how we can share that with others. In every rehearsal room and theatrical space that we’ve worked in since NBT, we bring that soul with us.

CAITLYN

NBT was the first revenue-generating Black arts complex in the country, capable of subsidizing their own performances. What is your vision for producing models (economically speaking) that would best support your theatrical visions?

TA-NIA

We've been dreaming up ideas around this a lot recently! At the moment, we're very interested in reimagining currency in regard to theatrical experiences. For example, we're interested in ways we can share our work with flexible ticket models—those who have funds can purchase tickets and those who don't can offer something else in exchange whether that's offering a cooked meal, leading a workshop another day, etc. In this same vein, we're interested in creating a community space where we can share our work, engage with our respective community through events and workshops, offer a safe space to just have a cup of coffee, house a community garden.

︎

Dreams in Black Major will be live streamed at Theatretreffen's Stückemarkt in Berlin on May 22. In fall 2021, A Map to Nowhere (things are) will be presented as part of Soho Rep’s Writer/Director Lab. Follow The Map Project @amaptonowhere.

Ta-Nia:

We are Talia Paulette Oliveras and Nia Farrell, collectively Ta-Nia, a theatre-making duo committed to challenging the limits of theatre to create unapologetically Blk spaces of liberation. As creators and performers, we focus on developing new work that foregrounds identity, collectivity, and celebrations of dreams. Since graduating from NYU Tisch, our work has been presented in Ars Nova’s ANT Fest 2019 and will be in Theatretreffen’s Stückemarkt 2021 (Dreams in Blk Major). Currently, we are members of the Soho Rep Writer/Director Lab and finalists for SPACE on Ryder Farm’s Creative Residency 2020 (A Map To Nowhere things are). We are multi-hyphenate artists who apply our interdisciplinary nature to the art we create in both process and product. Talia has collaborated with Musical Theatre Factory, Big Green Theater, Theatre Mitu, JACK, Mabou Mines, The Public, and BAM. And Nia has collaborated with Theatre Mitu, National Black Theatre, The Public Theatre Mobile Unit, and New Ohio Theatre. Learn more at: ta-nia.comCaitlyn Tella:

Caitlyn Tella is a theater maker and poet originally from the Bay Area. Her chapbook, Sky Cracked Open the Proscenium Frame, is forthcoming from DoubleCross Press. caitlyntella.com

December 21, 2021

COMMITTING TO THE FAKE: An Interview with Anh Vo

By CAITLYN TELLA

Caitlyn and Anh Vo discuss psychotherapy, performance, transcendence, and familial ghosts.

Anh stewing on stage, Summer 2021. Video by Caitlyn Tella.

Anh stewing on stage, Summer 2021. Video by Caitlyn Tella.I wanted to interview Anh Vo after watching this video of Red (For Communism). Performed at Judson Church in 2019, the dancer sails across the floor, skipping in clipped cadence, occasionally making perky, ceremonious leaps. I watched on my laptop, entranced by the lively near-precision of their steps and commitment to keep skipping for an annoyingly long time. As nothing new continues to happen, joy, set to communist revolutionary music, accumulates, and to my surprise, given the frequently bland conceit belying so much duration-as-content performance, so does a palpable lack of pretentiousness.

When the skipping ends, Anh jokes, “The white abstract part of the performance is over” and proceeds to attract an audience member to the open floor of Judson Church to play a little cross-examination game: “Have you ever been a communist party member?” “No.” ... "Have you ever been on the 23rd street of Manhattan?" “Yes.” “Are you aware the Communist Party USA headquarter is located at 235 West 23rd Street?” (Audience laughs), etc.

At the top of that performance the lights go out and a voiceover of Joseph McCarthy espouses evergreen American beliefs that communists have no freedom of thought, no freedom of expression. In the dark of this historical trace, I ponder the levels of self-denial I have achieved to manage to pay rent.

Anh at Herbert Von King Park in Brooklyn, where this interview was conducted. Photos by Caitlyn Tella.

The first time we talked, Anh told me they were dealing with the ghost of their grandfather: in psychotherapy four days a week and also with a shaman. Anh had experienced profound technical difficulties before performing BABYLIFT at Target Margin in February—a memory for no audience named after Operation BABYLIFT, the 1975 mass evacuation of children from South Vietnam to the United States that resulted in a plane crash killing 78 of them. After spilling coffee on their laptop the day before the show, Anh realized they needed professional, high-order guidance from a shaman before scheduling any further performances. “At least that’s how the message got translated into my consciousness,” they said.

Since then, I’ve seen Anh perform twice. In sweaty New York summer they stewed an aromatic soup on stage. Then, as if trapped in a spell, repeated an elegant loopy step, producing increasing sweat. In autumn at MOtiVE Brooklyn, I saw their latest iteration of Non-Binary Pussy, sexy propaganda fueled by Anh’s popstar persona, featuring video, intricate choreography and great raps like MY PUSSY: ZEN DANCE SLAPPING. YOUR PUSSY: BLAND STRESSED NAPPING.

︎

BABYLIFT at Target Margin Theater, 2021. Credit: Yekaterina Gyadu.

CAITLYN

What made you start working with ghosts in performance?

ANH

It was a very unconscious decision. I think people here have no relationship to death and in Vietnam there are many rituals around the dead and war. It felt culturally important.

I come from performance studies which theorizes this fake-real relationship—how the fake is always the real and the real is never truly real. So I decided to fake trying to conjure ghosts. I went into my memory of my father performing these traditions and just stayed with that memory. I didn't try to google it. I had no idea what I was doing. I was like, “am I offending ghosts right now?” And that’s the price I would have to pay.

CAITLYN

Did you have a sense of—oh maybe I’m on to something? How did you register a connection?

ANH

Things gained clarity over time. For BABYLIFT I did a five hour ritual before the performance, very rhythmical. And a lot of singing. That was the part where the ghost was there. My grandfather. I almost fainted. In Vietnam we usually call people who are susceptible to ghosts and haunting as having “weak aura.” People who are always pale and dizzy—fainting is one of the signs that the ghost incorporated into your body.

CAITLYN

When you were growing up were you interested in your ancestry?

ANH

Not really. That’s where the paradox is. I had to leave Vietnam to have some awareness of how important war is, for example. We never talked about war. Why would they talk about it? I know nothing of my mom’s life pre-1975. Or really, pre-1986 when capitalism was integrated. We just have an idea that there was a lot of suffering. Only when I left I felt the haunting of the war nagging at the present, informing why people are the way people are in Vietnam. But I have no investment in trying to find the truth of my family’s history. I think more of a unit where historical relations play out, where there’s this suffocation to death of a certain way of life, a certain possibility that could have gone somewhere else in history. Instead the U.S. suffocated it. Now here we are.

CAITLYN

So you’re exploring this undiscovered place that could have existed—the unknown.

ANH

I think so, and that’s why it’s so speculative. I don’t want to do an anthropological exercise of interviewing my parents. That’s not how the truth comes out. It comes out in random ways, so my sensibility now is to pay attention to how these historical traces emerge.

CAITLYN

Speaking of traces, you use a lot of repetition in your work. How do these things form?

ANH

I think it has to do with ritual. I’m drawn to repetition of very small movements. Committing to the repetition weakens your connection to this world and you transport somewhere else.

CAITLYN

Would you say it’s like a trance?

ANH

Very much like a trance. Like, transcendence. The shaman said, “I don’t know how dance works, but when I see you dance I see you leave your body.” And my analyst really dove into that. She’s like, “Hmmm, you know, a lot of people describe a traumatic experience in terms of leaving the body and watching it from above.” She connects so many things to me leaving my body. I have a very clear investment in transcendence. Devising techniques to transcend myself. I black out every time I perform.

CAITLYN

What’s your relationship to the audience in all that?

ANH

I’m really invested in asking, “Why are we watching these things? Why do you have to show it to somebody? Why are people watching me do this?”

BABYLIFT at Target Margin Theater, 2021. Credit: Yekaterina Gyadu.

CAITLYN

Sounds like those questions motivate you, but they could easily be—

ANH

Debilitating? The opposite, it’s very motivating. For me theater is a very colonial structure—the watching, the expectations. The audience stares, they sit in the dark, people sit in silence, as if they don’t exist. The invisible eye is so violent. Especially when it comes to me working with these Vietnamese materials, that anthropological gaze is so annoying to me. This curiosity of “art that is exotic.” Of course it’s subtle, but as a performer I feel it so clearly. That informs why I don’t let people sit and watch in peace. (Laughs) They have to be implicated in the work. I want to lean into the power dynamic, make it explicit.

CAITLYN

Do you think sexuality is part of how you do that too?

ANH

Oh yeah, 100%. The way I approach sex in my work is actually very psychoanalytic. Elusive, unreachable. In analysis, sex has a lot to do with repression, especially repression of infantile sexuality which is more sensational. They say that as an infant your body is an erogenous zone, open to inspiration, sexual possibilities, sexual potential. And then they say that as you grow up there’s discipline, punishment, shame coming in that force you to repress your infantile sexual surge. Of course you can never fully repress it, so it comes out—in symptoms, in dynamics.

CAITLYN

The humor in your work is also very unexpected and direct, it feels improvised.

ANH

Yeah, it just comes out. Usually the way I work—I don’t choreograph. I sit in the studio and develop what I call repertoire. I have a repertoire of movement, of narrative, of moments. That’s how I improvise. I’m much more interested in durational form where the repertoire can actually be responsive to the moment. Although I feel like with Non-Binary Pussy it’s going to be precise, it’s going to be like dancey dance. A lot of audience engagement too.

CAITLYN

Getting the audience to dance?

ANH

Paying them to. I have to have enough money first. (Laughs.) Paying people on the spot.

CAITLYN

Then they can feel like it was their autonomous choice.

ANH

I don’t think there’s autonomy in a performance space. I hope to create a communal space where people are not so fixated on this boundary of you and I. There are other models, more productive to risk taking and play.

CAITLYN

That’s your agenda.

ANH

It is. I use the word propaganda. I want to create a space where people feel compelled enough to play with me. I never just force, I draw them in—it’s a difficult task. You’re watching me, I’m giving you all of my existence right now, I’m asking a fragment of yours. Reciprocation. That’s why I hate “audience participation.” Asking the audience to volunteer and shit. Acting like you’re inconveniencing the audience, whereas it’s always the fucking audience that’s devouring you.

CAITLYN

That’s a good word.

ANH

They devour you with their gaze.

Film stills from a video version of Non-Binary Pussy by Anh Vo.

CAITLYN

What do you make of persona?

ANH

I definitely have characters, but not explicitly. Each character is a repertoire to me.

CAITLYN

Is it a defense mechanism against the audience’s gaze? (Laughs.) That was a very psychoanalytic way to put it.

ANH

(Laughs.) I think defense mechanism is part of it. A mask does that. It's an external thing that protects your inside but also manages to give you access to the inside you don’t know as well. Non-Binary Pussy is very clear pop star. I felt I needed to embody a charismatic revolutionary. I used to want to be a revolutionary leader, that’s where I draw from.

︎

ANHThis analysis process has been fucking me up.

CAITLYN

How long have you been doing it?

ANH

Nine months. I’d never done therapy before. Classic Scorpio. The first therapy I do has to be four times a week. I would never say “I work with trauma.” Of course I do, but the word is overused. The way people mobilize the word as some sort of description of a traumatic event doesn't get at the obliqueness of trauma—how it always shows up when you don’t expect it and how you never know what your real trauma is. That’s the point of trauma! It exceeds your comprehension. It comes out as repetition, as action. That’s something so radical about psychoanalysis—they don’t try to know. Of course the eventual goal is awareness of your patterns, transforming them to a point where it’s healthy in your life.

CAITLYN

Do you get the sense of your analyst as an audience, having control over you?

ANH

A performance space is very similar to what they call transference—the space between me and the analyst and what happens there. She’s not explicitly the audience, if anything she’s the performer. She’s fucking with me. I don’t know anything about her. The analyst has to push you beyond your boundaries and I get very frustrated. I feel very persecuted. That’s her word. A little bit violated. But it’s fundamental to the analysis process because you have to be pushed beyond your resistance, because you always resist their interpretation. That curious connecting of different events—I fuck with that. But sometimes she gives an interpretation and I am just like, “What the fuck.” But then I sit with it. And I feel like that’s how I work with audiences.

CAITLYN

It sounds like it acclimates you to not knowing yourself.

ANH

Yes, I talked with a college professor recently and she was saying a lot of psychoanalysis is about not trusting yourself. Learning to not trust yourself.

CAITLYN

That’s radical.

ANH

It’s really radical. To not trust yourself. (Laughs) Of course you cannot trust yourself! You cannot trust the stories you tell yourself about yourself.

BABYLIFT at Target Margin Theater, 2021. Credit: Yekaterina Gyadu.

CAITLYN

So what do you stand on?

ANH

Exactly—the standing on is always some sort of illusion, a coping thing, to help you move through life. I was very shocked hearing from my analyst that the club, which is a place I dearly love, is a space of mania for me. Shocked. Of course, all the fucked up kids turn to the club, turn to the night. It makes sense. People need that sort of escape, or manic transcendent euphoria, the ones that have been fucked up by society. That’s where I started dancing, really drunk with music. Being in a crowd. Blacking out.

CAITLYN

It’s very Dionysian.

ANH

Yeah yeah yeah. Very Dionysian. My work does strive for that place.

CAITLYN

If you didn’t have that outlet it would be a pathology.

ANH

For me, that’s where beauty is. I see her point. But I still believe in transcendence, I still believe in leaving my body. I definitely want to—I was going to say “do something” about this mania thing. But the whole point is if you do, you’re in the manic mode (Laughs.) I often try to do instead of feel. Which, yeah, in order to be a productive person you can’t feel too much.

Anh Vo:

Anh Vo is a Vietnamese choreographer, dancer, theorist, and activist. They create dances and produce texts about pornography and queer relations, about being and form, about identity and abstraction, about history and its colonial reality. Currently based in Brooklyn, they earn their degrees in Performance Studies from Brown University (BA) and New York University (MA).Their choreographic works have been presented nationally and internationally by Target Margin Theater, Dixon Place, MR @ Judson, Brown University, Production Workshop, Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo (Madrid), greenroom (Seoul), Montréal arts interculturels (Montréal), among others. Their artistic process has received support from Brooklyn Arts Council, Foundation of Contemporary Arts, Women and Performance, New York Live Arts, Leslie-Lohman Museum, Brooklyn Arts Exchange, Jonah Bokaer Arts Foundation, Tisch/Danspace, and the Performance Project Fellowship at University Settlement.

As a writer, they are the founder and editor of the performance theory blog CultPlastic, the Co-Editor of Critical Correspondence, and a frequent contributor to Anomaly. Their writings focus on experimental practices in contemporary dance and pornography. www.anhqvo.com

Caitlyn Tella:

Caitlyn Tella is a poet and performer based in New York. Her poetry appears in Fence, Witch Craft, Dirt Child, Nat. Brut and MARY: A Journal of New Writing. She has two chapbooks forthcoming, from Double Cross Press and from Mondo Bummer. www.caitlyntella.com

March 26th, 2021

The Performative Self: On the Work of Leeny Sack

By CAITLYN TELLA

Caitlyn talks to Leeny Sack about spilling your guts, creativity as procrastination, therapy, and excavating intergenerational trauma through theater.

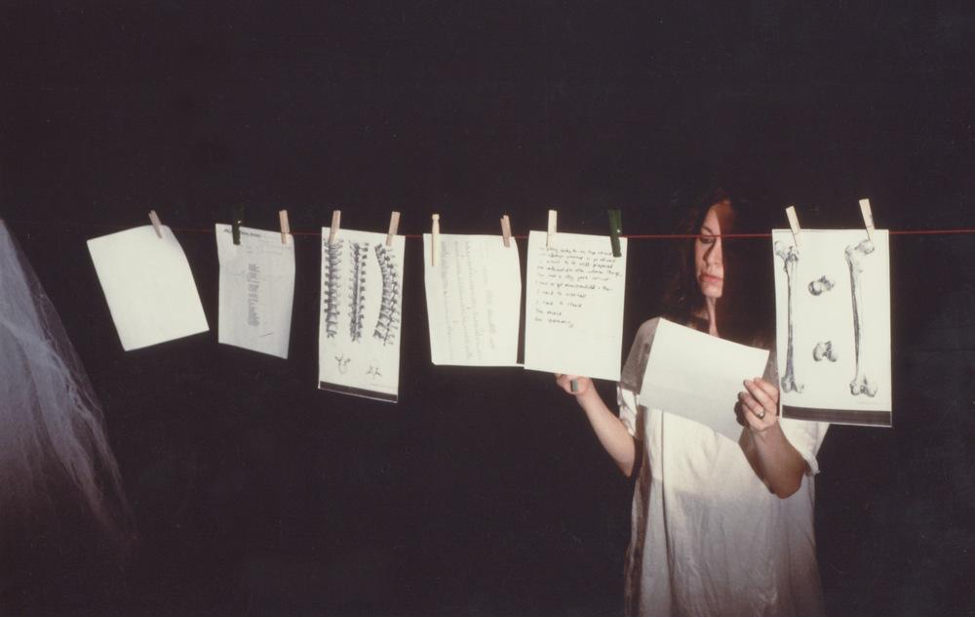

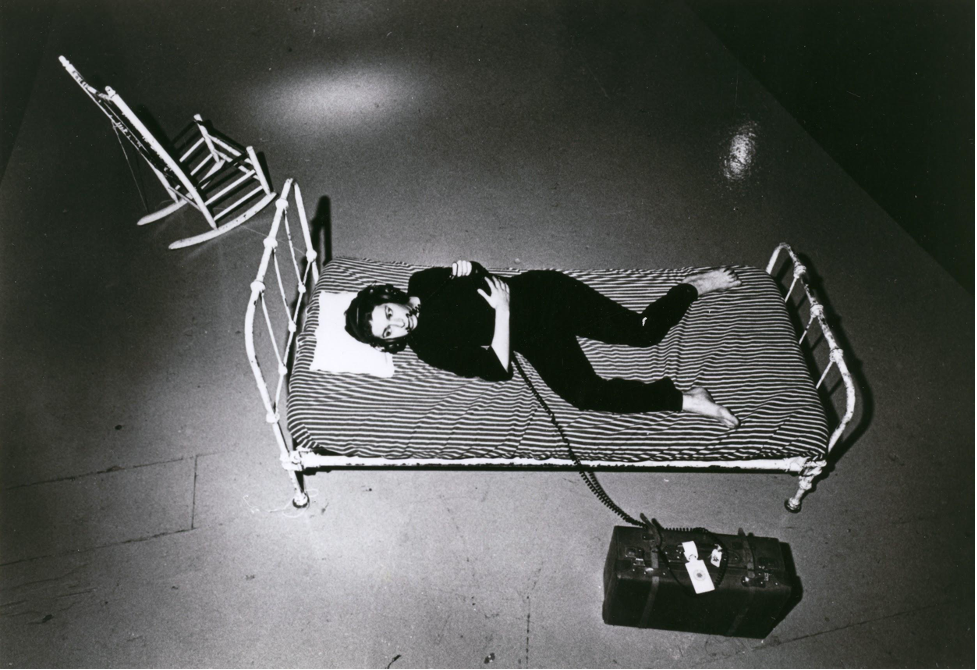

Leeny Sack in Our Lady of the Hidden Agenda. Photo: Jane Bassuk

Leeny Sack in Our Lady of the Hidden Agenda. Photo: Jane BassukAll actors are terrified that they are bad actors, so they try hard to be truthful––a trap––because effortful verisimilitude reads as bad acting. The TikTok meme “What’s an acting performance that was so good you forgot it was acting?” highlights this phenomenon. Whether stitched with sincere, ironic, or correct answers to the question, the performance of the meme itself reveals the conflation of acting and psychological realism in cultural consciousness––good acting being the ability to conceal artifice, bad acting the failure to do so.

If good acting is marked by Oscars, then why do all Oscar clips scream: I’M ACTING? Instead of passing as straight (the literal jargon for this kind of performance in theater is “straight play”), “good acting” should be recognized as the highly stylized form it is: psychological realism. The cultural premium placed on this style and its codified gestures (think, STELLA! et al.), warps the perception of what emotional truth must look and sound like to be considered real and good.

When concepts of self hinge on psychological terms, “I” don’t get much leeway, and the question that performers are primed to ask—Who am I?—has only obvious (boring) answers. Antonin Artaud, a dramatic obsessed with liveness, wrote, “Psychology, which works relentlessly to reduce the unknown to the known, to the quotidian and the ordinary, is the cause of the theater’s abasement and its fearful loss of energy.”

For performing artist Leeny Sack, psychological realism couldn’t be further from the truth. Born in Brooklyn, Leeny dropped out of Julliard in 1971 to join The Performance Group, an experimental theater company led by Richard Schechner that focused on actors as sources of dramaturgy rather than interpreters of fictional characters. When the troupe eventually split and morphed into The Wooster Group, she developed a solo career. Her body of work has been mythologized under the title “The Performative Self.” It interrogates concepts of self, not by crafting chameleon personas nor by shedding masks to uncover the “real me,” but through ongoing engagement with performance as a consequence of living.

A couple years ago, afflicted by romance, I fell lifeless under the weight of fantasy. I’d known Leeny as a teacher and flew to see her in hopes she could help administer the performative like a medicine. I wanted to find a performance to free me from fantasy.

I recently spoke with Leeny again for the first time in a couple years. Here is our conversation about her work.

Leeny Sack as Kattrin in The Performance Group's production of Mother Courage and Her Children, directed by Richard Schechner. Photo: Clem Fiori, 1975

CAITLYN

You once told me that when you performed your underwear would get completely soaked because you were so aroused.

LEENY

I would get so wet. Because performing was such a full being engagement, everything was flowing. Eros. Life force.

CAITLYN

Have you experienced that life force in the past year?

LEENY

Maybe where I’ve experienced it most extraordinarily was with [my dog] Moose’s dying and death. The life force in the presence of death was astounding.

CAITLYN

How did you ritualize his passing?

LEENY

Some of the usual bells and whistles--literally, bells, candles. Prayers kept coming through. And this extraordinary tension between letting him go and holding him, and knowing I had to get out of the way to let him go. His body was here for almost 24 hours and I would touch him and feel the change in his body temperature, his literal dead body temperature, and watch and feel the--what do you call it when the body stiffens?

CAITLYN

Rigor mortis?

LEENY

I would watch the pain of the suffering, the illness, leave his face. It was an extraordinary, heightened time. After he died, and since, his spirit body has come many times. If I still had doubts about afterlife, I don't anymore. It's so palpable. A simultaneity of warm, loving presence. I don't have language for that.

Moose and Leeny at the Ithaca women’s march, 2017. Photo: Hayya Mintz

I read in Michelle Minnick’s work that your desire to be an actress when you were young was to become immortal so you wouldn't die an anonymous death--

LEENY

Very much in relation to the Holocaust. Yeah.

CAITLYN

What drives you as a performer now?

LEENY

Hm. The great and very challenging disentanglement from my conditioned ideas about “performing.” The last piece I made, Subtitles, Signage, Signifiers, and Cogitations, I spent most of the month leading up to it in panic and anxiety. And, “How can I get out of this?” That was my preparation. But I'm working differently, not so much detailed scoring and rehearsal. Mostly object work and writing. What it means to be finished is different now.

CAITLYN

My whole creative process has been procrastination, then I'll randomly sit down and do something very quickly. I pretend the procrastination is some kind of gestation.

LEENY

It is, it's an incubation state. And the stuff around it, even the word procrastinating, is somebody else's word, and entrains all the ideas of making work and who we should be and how one is supposed to work. The grip of those ideas has deeply lessened during this time. I told you about the mucus plug, right?

CAITLYN

You told me I need to unplug the mucus plug and connect my sexuality to the earth.

LEENY

It's interesting you remember it that way.

CAITLYN

What did you mean?

LEENY

For a number of years I’d been feeling there was something in the way of my full work. A friend had a baby and she was saying something about the mucus plug. When she said that phrase, “mucus plug” I thought, oh my God, that's it! Somewhere in my belief systems I thought the energy of creative movement moved up and out. I had it directionally off. It was about birthing it back into earth, not going up into the heavens. Since then, my “energetic mucus plug” has slowly begun to dissolve. What I have yearned for is more accessible to me and I'm more out of the way of it.

CAITLYN

Do you relate the mucus plug to confessional forms? Like, spilling your guts out onto the stage.

LEENY

“Spilling your guts out” is a very personal thing. You're talking about accessing and “expressing” something personal. I'm talking about being able to get out of the way of things that are coming through. Maybe those things come through the word “I”, but it transcends that. When performing has really worked for me, it's this strange paradoxical thing of--look at me not being me. Look at something coming through me.

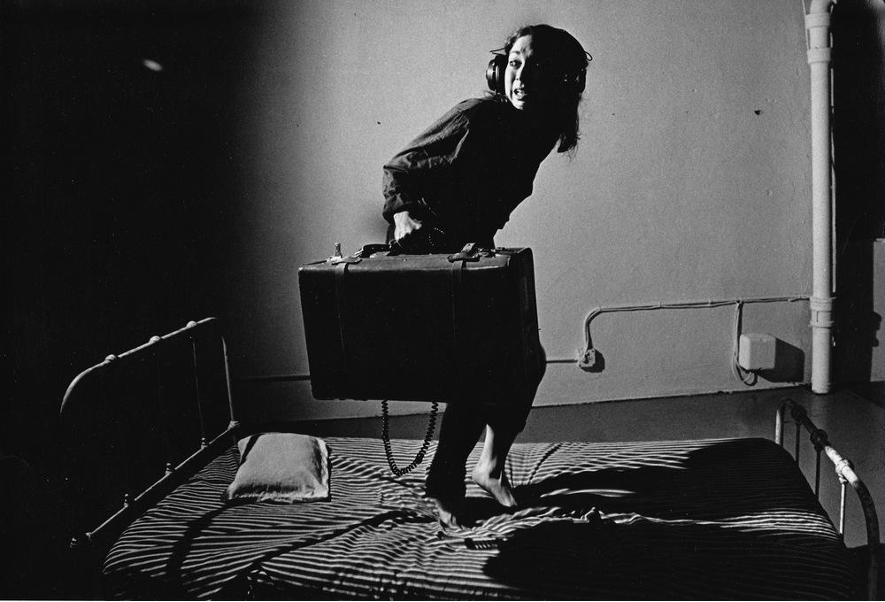

Leeny Sack in The Survivor and the Translator, 1980. Photo: Stephen Siegel

Leeny Sack in The Survivor and the Translator, 1980. Photo: Stephen Siegel

CAITLYN

The theater company provides structure, and the director provides structure, and the character too, but when you left The Performance Group you didn’t have any of that. When you started working on The Survivor and the Translator, you were alone.

LEENY

Yeah. I started in a studio alone, naked with a ratty old flannel gray blanket. And I didn't have texts yet.

CAITLYN

Was your intention to make a performance about trauma?

LEENY

Yeah, very much. First I thought I would do a piece on women, madness, and God. Rather large. I thought, how have I encountered those? That brought me back to being a child of Holocaust survivors. And that's the subtitle of the piece “a solo theater work about not having experienced the Holocaust by a daughter of concentration camp survivors.”

CAITLYN

How did you go from lying in the unstructured darkness to--

LEENY

I was inviting in the world of the Holocaust. It was so dark. To open to the deep, inherited memory and the deepest imaginable--I thought, no, no, no, I'm not gonna get through this … well. So I shifted and, completely antithetical to all my training and all my practice till then, I wrote. There was a great typewriter store on the upper West side and when I decided that I needed a typewriter I went up there and as I was walking in Elie Weisel was walking out. I thought, “a sign!” I bought this wonderful little electric Olivetti. The typewriter gave me focus and I wrote for months, researching translation, thinking how am I going to tell this?

Leeny Sack in The Survivor and the Translator, 1980. Photo: Stephen Siegel

Leeny Sack in The Survivor and the Translator, 1980. Photo: Stephen Siegel

CAITLYN

In the performance, your body is a vessel for memories that go beyond your first-hand experience. You are also the translator of those memories, translating between languages, generations, cultures, from memory into performance itself. Your body contains many voices. At one point the Survivor’s voice screams in Polish as the translator continues to translate in English, calm, matter of fact, split-off.

LEENY

The stories were imparted to me in Polish, or sometimes in accented English, or not good English, and also in silence. So that’s how I told it. One day my grandmother came over and started talking, as she often did, about the camps and the war. I turned on my tape recorder and when I transcribed it I tried to translate it into correct English. I would call my mother and say, “How do you say this in English, exactly?” At some point in transcribing I thought––why don’t I just get it down roughly, and then I'll fix it later. So I started listening and transcribing literally--out of syntax, “uh,” “Hmm,” silence, circularity, memory lapses. When I looked at it, I saw that this was the writing I was trying to get at all these months that I couldn't quite get. The space between the words. The failures of language. I threw out most of the writing that I had and began working with that text.

CAITLYN

In Therapy as Performance you strip off another layer of character. In that piece you staged real therapy sessions with three different therapists in front of full audiences. That piece makes me think about the deceit of self-concepts, how even in therapy, with its premium on honesty, whenever you tell your story, it’s contrived, and how confining it feels to only have words to tell your story.

Therapy As Performance (2018) video still. Leeny Sack, Moose, Jeff Collins, LSW, Meditation Retreat Leader.

Therapy As Performance (2018) video still. Leeny Sack, Moose, Jeff Collins, LSW, Meditation Retreat Leader.

LEENY

One of the things I was thinking about over time was exactly what you're talking about. The role of the characters of ourselves. I made lists of what roles I’ve played in the theater, what roles I’ve played in life. They got more and more specific, so it wasn’t only “daughter,” it was “my mother's daughter.” I just kept adding to that list. It does go on.

CAITLYN

Can you talk more about “astrology as performance,” “genetics as performance,” “preparing to die as performance?”

LEENY

Nope.

CAITLYN

Why is it interesting to you to frame those things as performances?

LEENY

The blurring between art and life? It's not a blurring, it's actually very clarifying. As the astrologer Caroline Casey said, “If we don't ritualize, we pathologize.”

Leeny Sack:

Leeny Sack is an interdisciplinary performance artist, writer, postmodern ventriloquist, and originator of The Performative Self™. Her works on identity, including The Survivor and the Translator, Straight Man, PATIENT/ARTIST, and Therapy As Performance, are part of a 4-decade body of work addressing performance as medicine. She has performed extensively throughout the U.S., Europe, and in Asia at venues including the Venice Biennale, The Edinburgh Festival, The American Dance Festival, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the first World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors. She was original faculty of New York University’s Experimental Theatre Wing (ETW), faculty at Naropa University’s Theatre: Contemporary Performance program, and cofounder of Pangea Farm retreat center for contemplative and healing arts. Sack is a certified Master Teacher of Kinetic Awareness®, the somatic practice originated by choreographer and intermedia artist Elaine Summers. She currently resides and teaches in Ithaca, NY, where she frames her work as Counter Stage, an intermedia performance series that takes place on her kitchen counter.leenysack.com/Caitlyn Tella:

Caitlyn Tella is a theater maker and poet originally from the Bay Area. Her chapbook, Sky Cracked Open the Proscenium Frame, is forthcoming from DoubleCross Press. caitlyntella.com

February 12th, 2021

The Impossible Realm of Embodiment: On the Work of Haruna Lee

By CAITLYN TELLA

Haruna Lee speaks to making theater on Zoom and offers a writing exercise into psychic landscapesWhat makes “~*real*~” theater so thrilling is the sensational feedback loop between actors and audiences, woven into the fabric of shared space and time. Unaided by the literal porousness of space that transmits breath and laughter, theater on Zoom plays out more on a psychic plane, which, actually, has its own erotic merits. Like masturbating, actors can only imagine they are being seen.

As far as theater architecture goes, Zoom’s fourth wall collapses into the first, second, and third walls, creating a very flat earth experience for everyone involved. An intense suspension of disbelief is required to get into it. Or maybe it’s an engagement with belief––belief that this is, in fact, a gathering, that I’m not just alone with my laptop watching, through the window, actors, who are also alone, do their thing.

Playwright and director Haruna Lee, whose body of work in experimental theater spans a decade (and recently earned an Obie for the conception and writing of Suicide Forest), took this most rudimentary constraint on the art form as an opportunity to exploit the very core of live performance in Beyond the Wound is a Portal, a production they helmed as a visiting artist at Stanford last fall. In a feat of collaboration with seven student writer/performers, the choreographer Sarah Ashkin, and musical director Sheela Ramesh, the entirely original Zoom show, created remotely, found ways to, as Haruna said, “reach through the box within the box and touch each other.” In Emergent Strategy, a book Haruna cites as an influence, adrienne marie brown portends, “the sacred comes from limitations.”

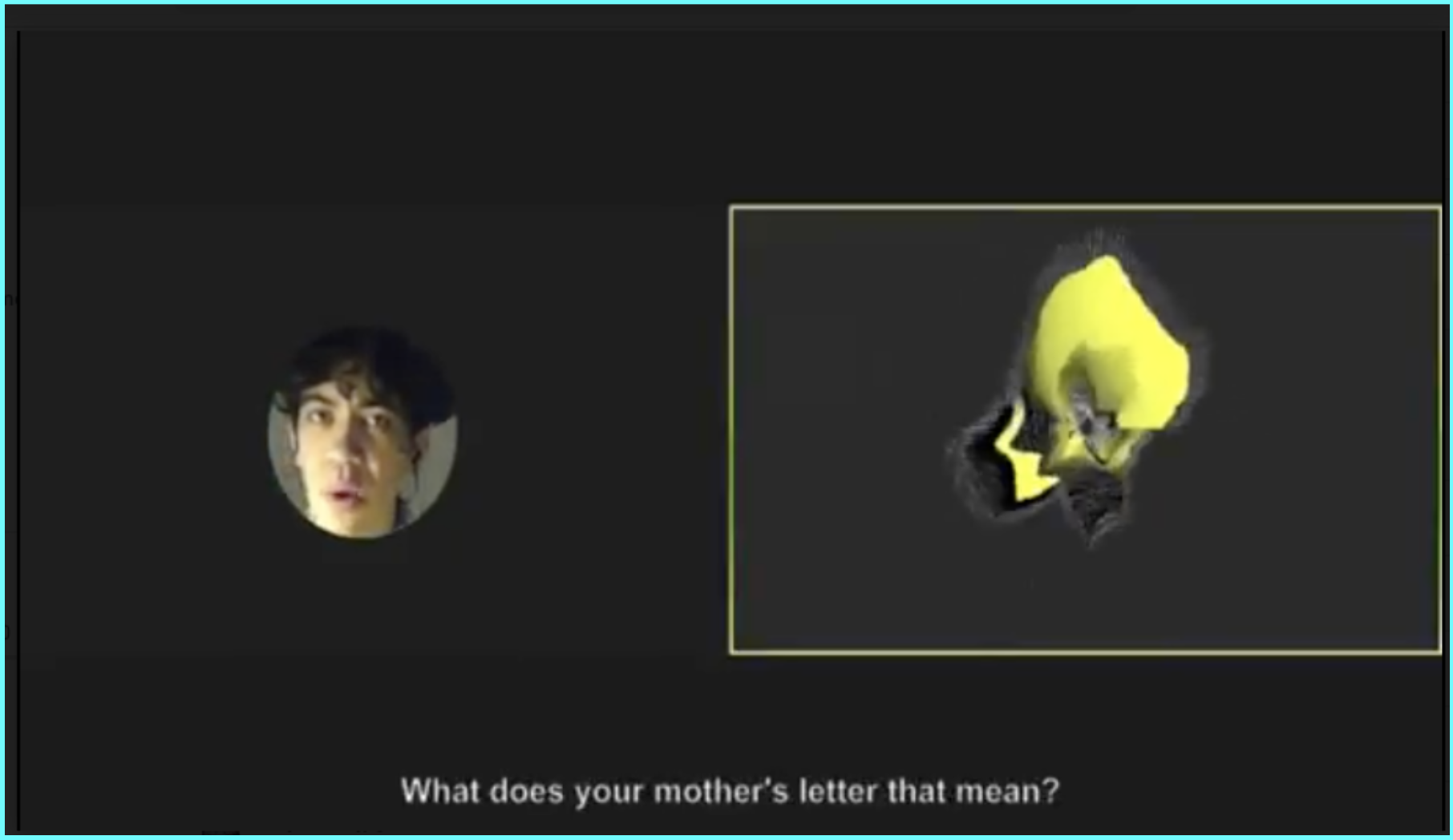

Beyond the Wound is a Portal digital backdrop by scenic designer Carlo Maghirang, depicting an altar of ritual objects chosen by each performer. The show was produced by the Stanford Department of Theater & Performance Studies in Fall 2020.

Beyond the Wound is a Portal digital backdrop by scenic designer Carlo Maghirang, depicting an altar of ritual objects chosen by each performer. The show was produced by the Stanford Department of Theater & Performance Studies in Fall 2020.JULIANNA: What is there on the moon that you can’t find here?

DIANA: Space.

-Beyond the Wound is a Portal

Beyond the Wound is a Portal opens on a familiar grid of mini-prosceniums, each performer tucked into the box set of their own home. Alexa (all the actors play versions of themselves) welcomes the audience onto the Zoom platform, “a place that is nowhere and everywhere at once,” before each actor goes around *the circle* to share a recent dream and the name of the land they stand on. This paradox, where everywhereness (a gaping yet loaded void) intersects with the actors’ specific contexts on colonized ground, activates the non-linear journey ahead.

The tidy Zoom boxes dissolve. Glass breaks, and one of the actors, in simulated miniature, free falls in darkness, then through clouds of wisteria. Frames distort and cohere into a variety of potent, psychic landscapes throughout the show, technically composed by layers of live and pre-recorded action, as well as surrealistic 2D and 3D animations. The actors enter cabins, tunnels, clubs, and cosmos like lucid dreams and navigate their mysteries through song. Singing functions like a sensory faculty—–it heightens the actors’ perceptions of grief, longing, and bewilderment lodged in each environment.

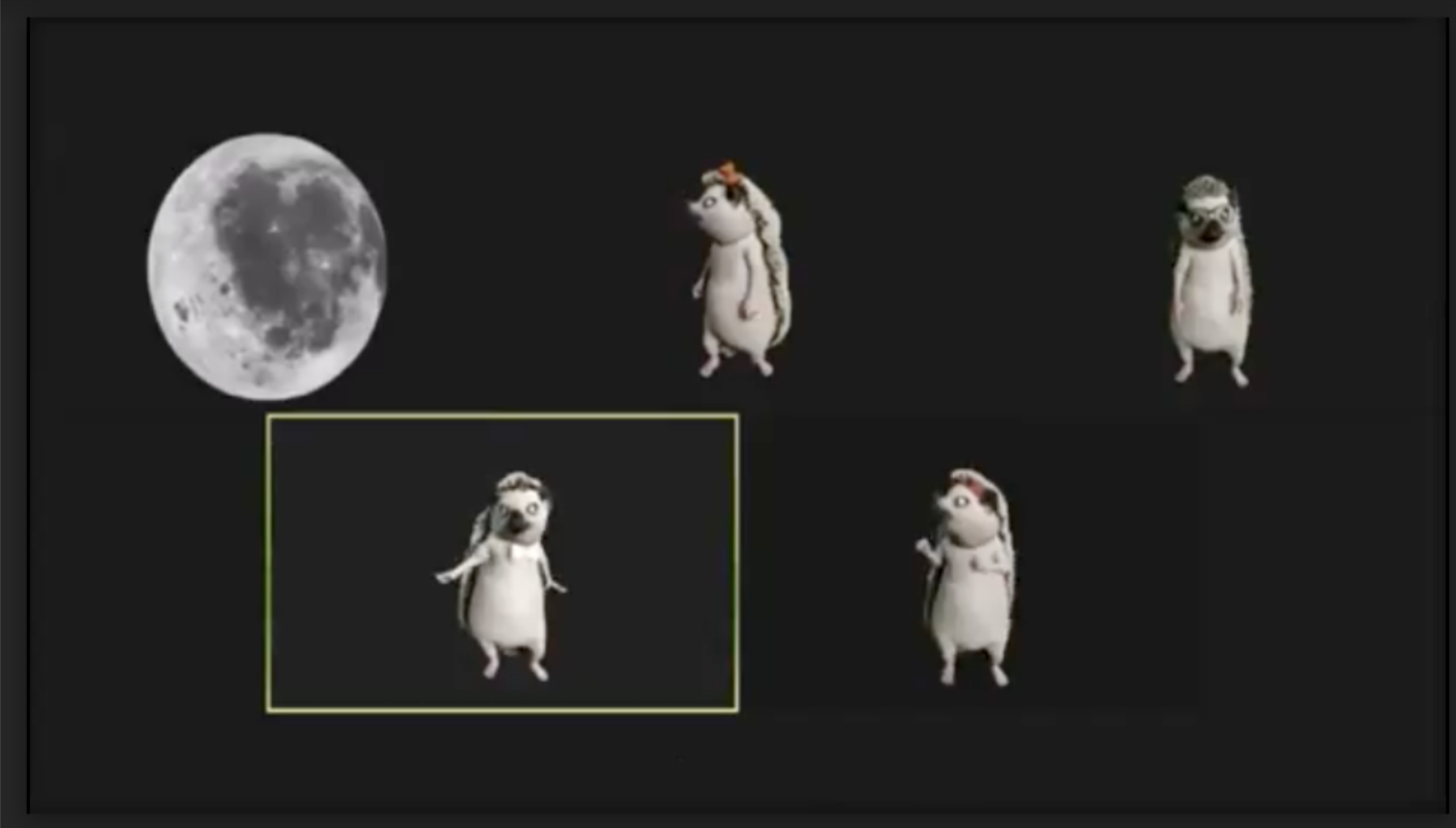

A dollhouse full of inexplicable hedgehogs contains a claustrophobic mother-child relationship.

A dollhouse full of inexplicable hedgehogs contains a claustrophobic mother-child relationship.

The mother, played by Julianna Yonis.

Club Waxing Gibbous, 2024. Surrounded by flailing limbs and broken beats, performer Alexa Luckey wakes up in the terror of a memory that encases and exposes her.

Club Waxing Gibbous, 2024. Surrounded by flailing limbs and broken beats, performer Alexa Luckey wakes up in the terror of a memory that encases and exposes her.

Morgan, grieving his mother, becomes trapped inside the loneliness of tunnel vision. “I want to go back to feeling safe,” he begs a globular, oscillating oracle, before a vaguely familiar tune catches his attention.

“We all sing it to ourselves sometimes,” quips the oracle. This moment reminded me how pain can feel so alienating and spacious at once. The tunnel disintegrates and opens on a new portal: the cabin where Morgan finds a letter his mom wrote to him before he was born. He sings, “I wish that she could smile at me one last time / then I would know / and at last she could go.” His voice embodies a mix of self-declaration and keening. Throughout the show, singing seems to separate the actors from their pain by giving it its own voice. As a voyeur, this was soothing to experience.

Video and 3D Design by Matt Romein.

In Diana’s dreamscape, they are on a quest to live where pain has no lineage. They end up on the moon. There, a bunch of hedgehogs worry they will miss the earth. Even if they do, Diana says, “I don’t think the myth that would welcome me back [to earth] has been written yet.”

Structurally tied to the ever growing, ever shrinking moon cycle, the show has no resolution, no final healing touch, even as we return to the familiarity of the Zoom grid. Of course not. There is only process and possibility, and myths yet written. When it ended, I felt spacious, as if I’d just spent an hour lying on the earth, gazing into the night sky. The next evening, I met with Haruna on Zoom to talk about the show.

︎

CAITLYN

The show made me feel incredibly soft. When it was over I thought it was odd that I’d gotten totally immersed in a performance on Zoom. I know the show was originally going to be in-person...how did you make something so intimate online?

HARUNA

Yeah, I echo that there was something so tender and sweet about what came from that particular group of artists. I think there's something to the impossibility of having to create embodiment digitally. The fact that this group was game to move towards that, even though the impossibility was crystal clear, might've been what birthed the tenderness. Without a sense of care and lovingness, I just don't think it would have been possible to create a brand new show.

CAITLYN

The care was palpable. Also, watching it felt like a time capsule of early pandemic.

HARUNA

Yes, we played with that idea so much, so it’s amazing that you say that.

CAITLYN

What was the beginning of the pandemic like for you?

HARUNA

In the spring, summer, and fall of 2020, the grief was huge. I was thinking a lot about wounds. I had just had this show Suicide Forest that got cancelled midway through March. My mother was in that show with me, and the trauma of having to close it and having to make quick decisions with my mom about where her body should be, where would be most safe—–should she stay in New York? Do we send her back to Seattle? And slowly realizing the dissolution of the embodied arts culture as we know it... all of that was hitting us in the moment, and it felt like fresh wounds.

CAITLYN

So how did you start working on the show? It was made from scratch, right?

HARUNA

Yeah. Creatively, our show started with adrienne marie brown's essay Dream Beyond the Wounds. In the essay, amb asks us to use our imagination as if it's medicine to dream beyond the space of just wounds. What are the possibilities when we do this? A lot of early writing prompts with the cast were based on imagining the landscape of a wound.

After writing, writing, writing—–scenes, monologues, songs—–we arrived at this place where we were like, how are we going to organize this? The cast was really drawn to the moon cycle as a structure for the piece itself. We started with the waxing gibbous and we ended on the new moon. And we eventually created this very ritualistic, abstract, imagistic dream logic piece.

CAITLYN

I kept thinking “beyond the womb is a portal” because there were a lot of mommy issues being explored.

HARUNA

I wasn't intending on bringing that energy into this work, but I think some of the cast members had read Suicide Forest and the idea of the monstrous mother, which is something I explore in that play, was really present. The hungry mother, the dark sides of mother, as well as the generous light sides of mother, were all at play.

I also picked up on the family relationships they were working through because they were no longer on campus. They were all back home in their childhood bedrooms. So, a lot of intergenerational workings seeped through, a lot of parent-child dynamics, and the residual pain from that. The death of family members was also present throughout the process.

CAITLYN

Yeah, it felt very courageous, and raw. I mean, the actors played themselves, well, versions of themselves. I thought it was interesting how it opened with that slightly awkward thing of going around a circle to introduce yourself. That threshold moment with a new group before you dig into the guts of whatever it is you’re about to do. I enjoyed watching the actors perform a kind of ease with discomfort in that scenario, or a mix of ease and discomfort.

HARUNA

There’s a sweetness there. Finding a common denominator felt really real in a time when things feel so fractured and people are carrying so much grief and stress and tension. The idea that we have to be productive, and not having space to release and let go. I felt the group working through the biggest, most human ideas we can all relate with. And that somehow created care, like, let's just care for everyone! Can we do that? Is that possible?

But something I learned is that community care can’t necessarily be a learning space. It has to be just plain care. Rest and play, not more work, not more constructive conversations on race and racial dynamics and how that plays out in this piece and all that.

Beyond the Wound is a Portal production still featuring (clockwise from top left) Emily Saletan, Alexa Luckey, Julianna Yonis, Morgan Gwilym Tso, Chloe Chow, Diana Khong, and Obed De la Cruz at center.

How do you work with images as a performance maker?

HARUNA

When I think images, I might actually mean landscapes. I think a location houses a collection of different images. In Suicide Forest, for example, I had just read Funnyhouse of a Negro by Adrienne Kennedy and was struck by the way she uses her own psychic space as the landscape of the play itself. I was really drawn to that as a prompt–—to find a dark psychic space that speaks to my Asian American identity. That led me to thinking about Aokigahara, which is ‘Suicide Forest’ at the base of Mount Fuji, and what a rep that place has from a Western viewpoint. I was interested in what would happen if that forest was actually full of possibility and love and reconnection with ghosts and mothers. Like, if it's actually an intergenerational space where the conversations that we could never have could happen. The first part of the play that takes place in the suicide forest is full of goats who are rock climbing!

CAITLYN

Oh! Maybe this is a good time to do a little writing exercise? I was hoping you could lead me through something you used in your rehearsal process to generate material.

HARUNA

Oh, yeah. I actually don't think I used this writing exercise for Beyond the Wound is a Portal, but it’s a writing ritual I return to all the time. I call it “The Cosmic Cellar.”

CAITLYN

When you go on these imaginary journeys, like in this writing prompt, do you fight with your brain about the images that come up?

HARUNA

Oh yeah, I think I do. I think I fight with my brain and play with it and sleep with it. That’s what's so beautiful about the image world—–it allows for so much messy simultaneity, and that's such a core of my… of me.

CAITLYN

Where does your life end and performance begin? Or maybe I mean, how do they overlap?

HARUNA

That is such a good question. Does my work create a shift in my lived reality? More and more I’m finding that's the case. That's what I'm getting off on in making art—seeing the ways the thing I make deeply impacts my lived experience and vice versa. My work continually moves towards a more relational, more community-based model. I just can't help it. I'm getting sucked into that.

My most recent collaborators are people I would want to be stranded on an island with. People I am so deeply inspired by and care about, their families and their livelihood. I’m grounding into how my sense of freedom and true, liberated self can be connected to somebody else's who is entirely their own human being. Really beautiful collaboration feels like a mirror of that, where we're allowing each other to be more free rather than less free.

CAITLYN

What processes or rituals have you been participating in lately?

HARUNA

Mmm, I think gathering is such an important ritual. This group came out of making Suicide Forest, which is the “Women-Trans-Femme-Non Binary Asian Diasporic Performance Makers Potluck.” Such a long title, but I feel with the first draft—just have all the words!

Women-Trans-Femme-Non Binary (WTFNB) Asian Diasporic Performance Makers Potluck (zoom version)

Throughout the year [this group] has been a touchstone for me—–the act of gathering and also [the fact that] within the group we’re actively coming up with rituals that help each other get through this time. We had one where we all, 30 or 40 folks, shared a word that describes something we're carrying in ourselves that we want to let go of. I wrote everyone’s words down on a piece of paper and went out to my yard and did a little burning ceremony with this piece of paper that had all of our words. As a group I think we realized like, “Oh, what that person needs to let go of is something I need to let go of too.”

Ritual objects Haruna keeps close.

CAITLYN

I think a lot more people have been dabbling in spiritual practices, like creating new solo rituals during quarantine. It's inspiring to hear you talk about a group ritual, a collective beholding. Having everyone there to watch makes it so powerful.

HARUNA

We really had to work up to that idea too. That group met a few times over the pandemic before we felt we could even go forward with this idea. We were like, “Wait, what would it mean for this group to perform this ritual over Zoom?” It didn't even cross our minds at first.

Beyond the Wound is a Portal production still.

Image created by Morgan Gwilym Tso.

Haruna Lee:

Haruna Lee (they/them) is a Taiwanese/Japanese/American theater maker, educator and community steward whose work is rooted in a liberation-based healing practice. They are committed to promoting arts activism and emergent strategies for the theater through ethical and process-based collaborations that challenge systems and legacies of power, while inviting the fullness of marginalized bodies and the complexity of lived experience to their practice. Recent plays include Suicide Forest published by 53rd State Press (Ma-Yi Theater Company and The Bushwick Starr), plural (love) (Soho Rep Writer/Director Lab; New Georges), and Memory Retrograde (UTR; Ars Nova; BAX). Lee is a recipient of an Obie Award for Playwriting and Conception of Suicide Forest, an FCA Grants to Artists Award, received the Mohr Visiting Artist Fellowship at Stanford University, a MacDowell Fellowship, the Map Fund Grant, Lotos Foundation Prize for Directing, and a New Dramatists Van Lier Fellowship. They were a member of the 2019 artEquity cohort, and are a co-founder and lead facilitator for the Women-Trans-Femme-Non Binary Asian Diasporic Performance Makers Potluck. They received their M.F.A. from Brooklyn College under the tutelage of Mac Wellman and Erin Courtney, and a B.F.A. from NYU Experimental Theater Wing. harunalee.comCaitlyn Tella:

Caitlyn Tella is a theater maker and poet originally from the Bay Area. Her chapbook, Sky Cracked Open the Proscenium Frame, is forthcoming from DoubleCross Press. caitlyntella.comNEW YORK, NEW YORK

EST 2020

︎

© THE QUARTERLESS REVIEW ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

EST 2020

︎

© THE QUARTERLESS REVIEW ALL RIGHTS RESERVED