May 27, 2022

Emailing Emna Zghal

By Addison Bale

[Author’s note: It’s fitting that Emna Zghal and I held this over email.

Normally we sit in her Bushwick studio surrounded by paintings in progress while sharing a meal, discusings poems, reading, and considering the differences in the translations of poems that Emna had in two or three languages. Up until this point, we have never spoken through writing beyond the occasional text message. Here we talk about the cross-influences of writing and artistic practice, following a short chain of emails into candid territory. Disguised in other topics, Zghal’s paintings are actually the silent centerpoints of our conversation through which all other matters can be considered. We discuss poetry, language, the art world, capitalism; the themes that contour-trace this artist’s life and work. ]

Normally we sit in her Bushwick studio surrounded by paintings in progress while sharing a meal, discusings poems, reading, and considering the differences in the translations of poems that Emna had in two or three languages. Up until this point, we have never spoken through writing beyond the occasional text message. Here we talk about the cross-influences of writing and artistic practice, following a short chain of emails into candid territory. Disguised in other topics, Zghal’s paintings are actually the silent centerpoints of our conversation through which all other matters can be considered. We discuss poetry, language, the art world, capitalism; the themes that contour-trace this artist’s life and work. ]

︎︎︎

Addison Bale <sayhey.adi@gmail.com> Feb 13, 2022, 1:42 PM

to Emna

Emna,

Remember sharing poetry over lunches? It was a short-lived arrangement but you still managed to show me such beautiful work, reading segments from The Tree, by John Fowles, and translations of Borges. I have his poem you read to me, "Ars Poetica," saved in my notes and, if I remember correctly, you have that same poem pinned to your studio wall. Can you talk about your relationship to literature in your life and practice as a painter?

*

Addison

︎︎︎

Emna Zghal <[...]@emnazghal.com> Sun, Feb 13, 7:30 PM

to me

Poetry lunches were great! Literature has always been central to my understanding of art. My most cherished memory of my late father is him reciting poems on all occasions, mundane or solemn—at the dinner table, commenting on the news, or at family events. As a child, I didn’t always understand the words, but his delivery made me feel he was articulating the Truth. When I became an artist, these experiences of poetry remained the aesthetic standard that I aspired to. In my undergraduate years in the school of fine arts in Tunis, I was devouring all the artist monographs I could put my hands on but sought guidance as an artist from poets like Adonis.

Arte Poetica—translated as Ars Poetica—by Borges both validates the beauty of infinity and of being lost. Poetry is immortal and poor, he says. The poem is an antidote for our current culture, which has little appreciation for the lost and poor. I named one of my paintings Arte Poetica in 2008. I often circle back to Borges to reconnect with what is important, sincere, and free of hype. I have that poem pinned above my palette table.

The Tree by John Fowles is a book I bought at the New York Botanical Garden, and I read it three times in a row, because I found in it so much validation of my instinctive relationship with nature and creativity. It taught me so much, and still does, on how to articulate these thoughts. Our relationship with nature is mediated by this drive to name and classify everything, which passes for knowledge. Little is left for the personal and subjective experience one can have of a river or a flower, an experience difficult if not impossible to articulate with the clarity of science. I was intrigued when he mentioned that his novels come from nature, and how such a statement was dismissed by scholars who thought that only literary influences and theories of fiction and the rest of that intellectual midden, as Fowles put it, are valid keys into literature. How foolish! He spoke of the small and tidy garden of Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist who invented the Latin naming and classifying system of plants and much of nature, as the opposite of a shrine for nature lover and akin to a nuclear explosion whose radiations continue to pollute much of the globe. I find this a terrific and terrifying image to be true.

︎︎︎

Addison Bale <sayhey.adi@gmail.com> Feb 14, 2022, 10:43 AM

to Emna

Can I see your "Arte Poetica"?

I love that anecdote about your father. Such a beautiful legacy to have left that in your childhood.

Borges' take on the Ars poetica is so good for it's attention to fluidity and futility; that poetry returns like dawn and sunset daily, as though begging us to see it; that it opens and closes the day, and maybe, for being an expression of daylight, is what begets our consciousness. So Borges explains without explaining, or rather, his examination of poetry is one that opens it up to be the most common, almost unthinking presence and yet so crucial to be the day itself. Borges allows for that subjectivity that we tend to lose when art and nature enters the classifications of academia or the institution. And this is totally what John Fowles seems to be getting at when he writes about trees and nature! And is, actually, what you are getting at too when you talk about painting.

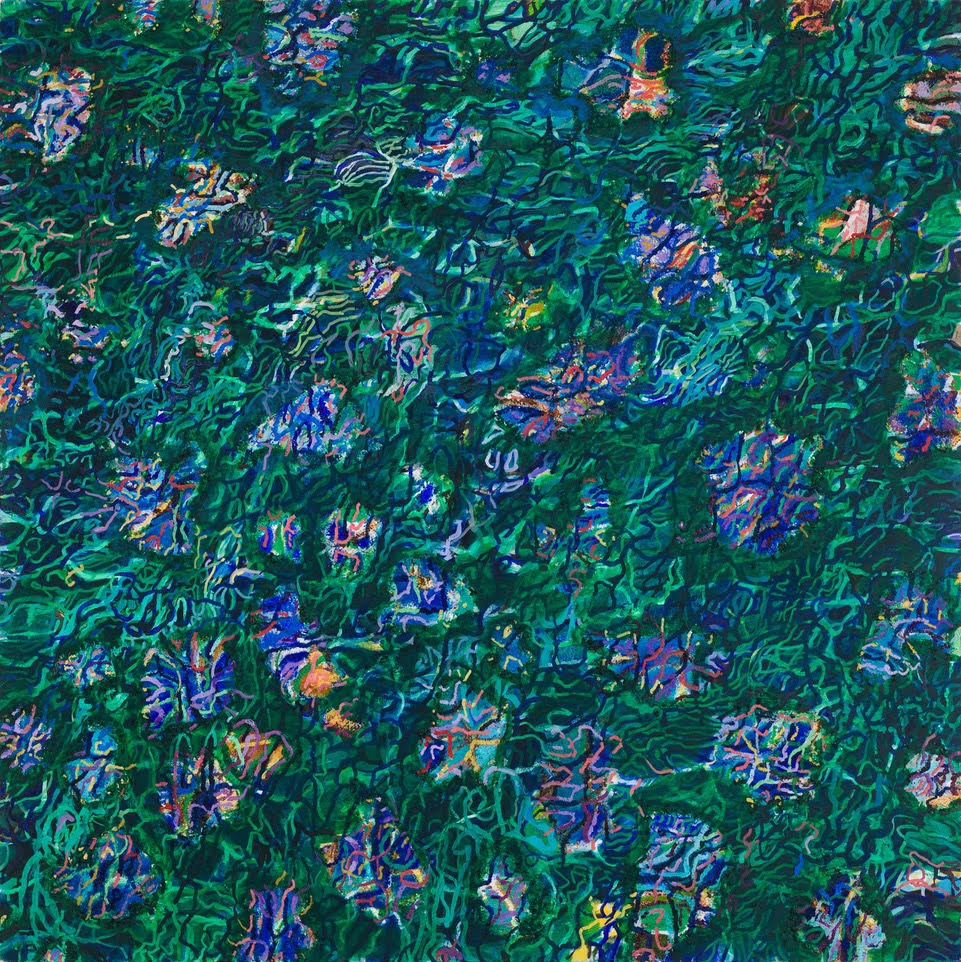

We've discussed before this overarching sentiment you reach for in art and life that you work within the unclassified and perhaps, unknowable phenomena around us, and that in doing so, there is the potential for much feeling and energy to interact with life through art. It seems that by clinging to the jargon of academia and the frameworks of art history, we relinquish so much of the intimacy between ourselves and art, whatever possibilities lie in that interaction. Your paintings, which are abstract but visually recall natural patterns (zoomed-out as in landscapes or zoomed-in as in shells or plumage) seem to be reaching for this conceptual experience of dwelling in the unknown in the myriad perceptions of pattern and randomness.

Do you see your paintings as images in dialogue with the literature in your life?

Are there ways that you are responding to your literary influences (including your father, including Adonis) somehow visually with paint?

︎︎︎

Emna Zghal <[...]@emnazghal.com> Tue, Feb 22, 10:25 AM

to me

Of course, here is my “Arte Poetica”.

It’s interesting what you brought up about the calcified frameworks of academia and the understanding of art and art history. Somehow the emotional experience of art seemed to have fallen by the wayside or relegated to an order inferior to concepts and art historical positioning. It’s as if that subjective experience of art (and similarly of nature) cannot be trusted, and therefore cannot be something that contributes to knowledge. I touched on this subject in my artist’s book Plato/Pineapple/Poetry/Painting. I see a parallel between Plato wanting to banish poets from his Ideal City (governed by reason) and contemporary art, which abandoned poetry as the language used to speak about art, in favor of theory (aka reason); and all that derived from that choice. All the talk of “subversiveness” does very little to actually undermine power. Many artists rail against capitalism, colonialism, and white supremacy; while little attention is paid to how nominally subversive conceptual art is very convenient for speculation. The making of art is outsourced to unnamed craftspeople or machines, and thus the possibility of failure is minimized and production maximized. The artist is now a brand and a studio CEO. It’s a far cry from being able to distinguish the hand of the master from that of the apprentice in yesteryears. What we lose, or lost, with this scheme is the sidelining of a whole realm of human intelligence. Being able to paint is a genuinely distinct form of human expression that is worth preserving, like dancing or playing musical instruments. Why should philosophizing crush all the rest? To the extent that painting survives, its validity is derived from an ideological content first and visual content second—if at all. Why would artists, critics, and art historians agree to this? I believe the answer lies in how intertwined the 1% is with influential institutions in the art world. Ready-mades are far more convenient for speculation. My ideas are heretical, not only because I was trained to paint and appreciate good paintings, but also thanks to the poetry that provides an anchor for me outside of the visual art world. Poetry emboldens me to operate with a different set of values.

In that sense, and to go back to your question, I don’t see my work as a response to literature. Poetry, and literature in general, schooled me in a certain form of knowledge that is not necessarily averse to reason, but one that fully embraces the full scope of experiences, beyond just what we can rationalize. I remember a quote by Adonis I had on my wall when I was an undergraduate student in Tunis: “Sufism as a method of knowledge.” He refers to the mystical poets of Islam. It struck me then and challenged my views on religion. Yet, seen through that angle, I understood what religion, as a form of human thought, had to offer us. Arguably some of the best music, architecture, or painting came from religious traditions. Poetry is different, the most important Arab poets, like Al Ma’ari and Al Mutanabi, were not religious. I say this because I think that poetry is also a method of knowledge. What I learn from poetry, and literature in general, is that personal experience and feelings anchor me in truth and artistic authority stems from a distinguished personal voice, ideals that the visual arts seem to have abandoned. I quote Ann Temkin, MOMA’s Chief Curator for Painting and Sculpture in my book Plato/Pineapple/Poetry/Painting: “Contemporary artists disavow transcendent goals of truth and beauty.” I think she’s right in her observation, yet I refuse to operate within that paradigm.

︎︎︎

Addison Bale <sayhey.adi@gmail.com> Mon, Feb 28, 2022, 1:03 PM

to Emna

To your point, the tentacles of capital and market-influences operate differently between the fine arts and literature. Speaking for poetry specifically, there is simply much less money involved and therefore much less money at stake in the world of poetry. Compared to the art market, poetry is still an artform relegated mostly to basement bars and living-room readings. Though perceptions of poetry are shifting with this generation, with social media and the work of new poets, it remains less commodified (compared to fine artworks) and therefore its value is always going to be fixed to the standard of a small book. I have often felt that this is actually a good thing for the art of writing, which is largely so exempt from the possibility, however faint, of explosive wealth. Though making money as an artist may be insecure, there is still the specter of prospect and value: paintings are worth x amount of hundreds or thousands. On the contrary, a single poem has no dollar value and its value in a collection is exactly the same on every platform, every mode of download or hard copy—as long as the poem can be read its value is immortal. So as an arbiter of truth, poetry seems to defy (slightly, and not to ignore its own trends and the machine of publishing houses) the erosion of "truth and beauty" through capital...I say this hesitantly though, still thinking as I type.

What is it that we do then? as painters that live by day-jobs, painters that mostly paint in obscurity, hustling for opportunities but likewise wary of the world we tempt to be more deeply involved with?

I consider your work as unique for its unwavering vision and persistence to pursue a practice that explores abstract painting as a reflection of or maybe distillation of the natural world, the imagery of the natural world and the information you take from it—so by painting and continuing to paint against market trends, who are you painting for? Is your practice solitary? Do you paint with a wish against capital? How do we exist as artists and work around that very art market you describe? Is it just a matter of gritting teeth and carrying on?

︎︎︎

Emna Zghal <[...]@emnazghal.com> Sun, Mar 6, 7:45 PM

to me

So many interesting questions there. Let me answer the straightforward ones first. Is my practice solitary? Yes, on some level. Sure. Solitude is crucial for me to achieve any depth. I mix with very few people to shield myself from the uninspiring. To get to your other question, who do I paint for? I am seeking an audience that shares similar values. I believe they are out there. This interview is part of an effort to reach out. I can’t paint on the desert island. What’s the point of self-expression if I’m not communicating with anybody? Looking back at the years when I stopped showing my work, I was blasé. I felt that this purportedly postmodern and diverse artworld had no tolerance for what I wanted to do. I was not ready to toe the line expected from “the native woman” and dish out cheap exoticism and victimhood stories. I felt beat up. I had no support, and still don’t, in my stubborn pursuit of this sort of abstraction. Yet! Yet here I am at it again. I gathered some strength, and I feel like I can take some punches again without being entirely knocked down. I sorted out my immigration status, and I have a day job that allows me to be in the studio. It’s far from ideal, but it’s a workable situation.

Do I paint against capital? No, that makes no sense. I steer clear from preposterous trendy and heroic claims of the sort. I do have a critical view of capitalism and how it functions in the artworld; and most importantly how it seeps through the mentality of art professionals: curators, art teachers, and artists. Books like “Privatising Culture” by Chin-TaoWu, “El Fraude del Arte Contemporáneo” by Avelina Lesper, and “La bêtise s’améliore” by Belinda Cannone are inspiring and empowering writings on this matter. Contemporary art posturing against capitalism is just that, posturing. The validity of a given work of visual art is no longer derived from careful visual examination, rather from statements, biography, and, above all, from market value. It’s lamentable that we, the art professionals, ceded our visual ground to literally stated ideas.

The allure of rebellion and subversiveness is superficial enough as to not threaten any established order. There’s no outrageous art Banksy can do that doesn’t feed the speculation frenzy of his work, or otherwise leads to a concrete social change. It’s important to be lucid about that. When truth is abandoned, the difference between saying and being no longer matters. There’s a classical Arab song that goes like this: Not all who tasted love, know what love is/ not all who drank wine are wine connoisseurs/ not all who sought happiness found it/ and not all who read the book, understand it. Truth matters to me, and so does discernment. I do believe nevertheless that making art and understanding it outside a framework of efficiency, purposefulness, and fame is a step towards lifting the limits put on imagining an alternative value system. That’s the value of being anchored in poetry, because, and as my friend Ammiel Alcalay says, poetry largely escapes capitalism. It’s not purposeful and efficient, it’s imaginative.

To go back to John Fowles and his critique of Linnaeus, it is legitimate to observe that the careful detached taxonomy of nature created all but an illusion of knowledge. Clearly, we’re hitting a wall. Knowing without humility and respect before the examined subject—in this case nature— is leading us on the path of self-destruction. Had we not sidelined emotions in the way we did, perhaps we would have been on a different path.

How do we carry on in these conditions? I didn’t know how to go on for a while. Without ever thinking it could happen, I strayed from the artworld. I got into Argentine tango, and it was like falling into a hole. I applied myself to learn an art form I had no natural abilities in, and at the end, I learned way more than dance steps. Tango taught me anew how to value craft, communication, disciplined practice, and preserving a tradition while being creative.

Now I feel I have a clearer vision of what I want to pursue. How to be a more poignant painter. In my case, the criteria is how to create images as mesmerizing and captivating as nature and its forms: vast landscapes or small shells; while bringing the viewer somewhere unknown and imagined. Being a better painter is more fulfilling an ambition than chasing the next clever idea. It’s not just gritting your teeth and keep on going; it is that of course, but also striving to stand on ever firmer ground intellectually to carry on. The gatekeepers might operate with different values, but you can tempt them to embrace yours. It is a worthwhile pursuit.

︎︎︎

Follow Emna:

Web: www.emnazghal.com

Instagram: @ezghalart

Emna Zghal:

Emna Zghal is a Brooklyn-based visual artist. She was trained in both Tunisia and the United States and has shown her work in both countries and beyond. Reviews of her exhibits appeared on the pages of the New Yorker Magazine, The New York Times, Artform amongst other publications. Noted public collections include Newark Museum, Flint Institute of Art, Yale University Library, The New York Public Library, The Museum for African Art, NY, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NY. She has received fellowships, prizes, grants, and residencies from: Creative Capital, The MacDowell Colony, Women’s Studio Workshop, American Academy of Arts and Letters, Cité Internationale des Arts (Paris) and others.Addison Bale:

is a writer and artist from NYC. His work is viewable online: https://adi-bale.com

More from “Shedding”:

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

EST 2020

︎

© THE QUARTERLESS REVIEW ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

EST 2020

︎

© THE QUARTERLESS REVIEW ALL RIGHTS RESERVED