October 17, 2022

Clothing for Poetry:a Conversation with Chelsea G.

By Addison Bale

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

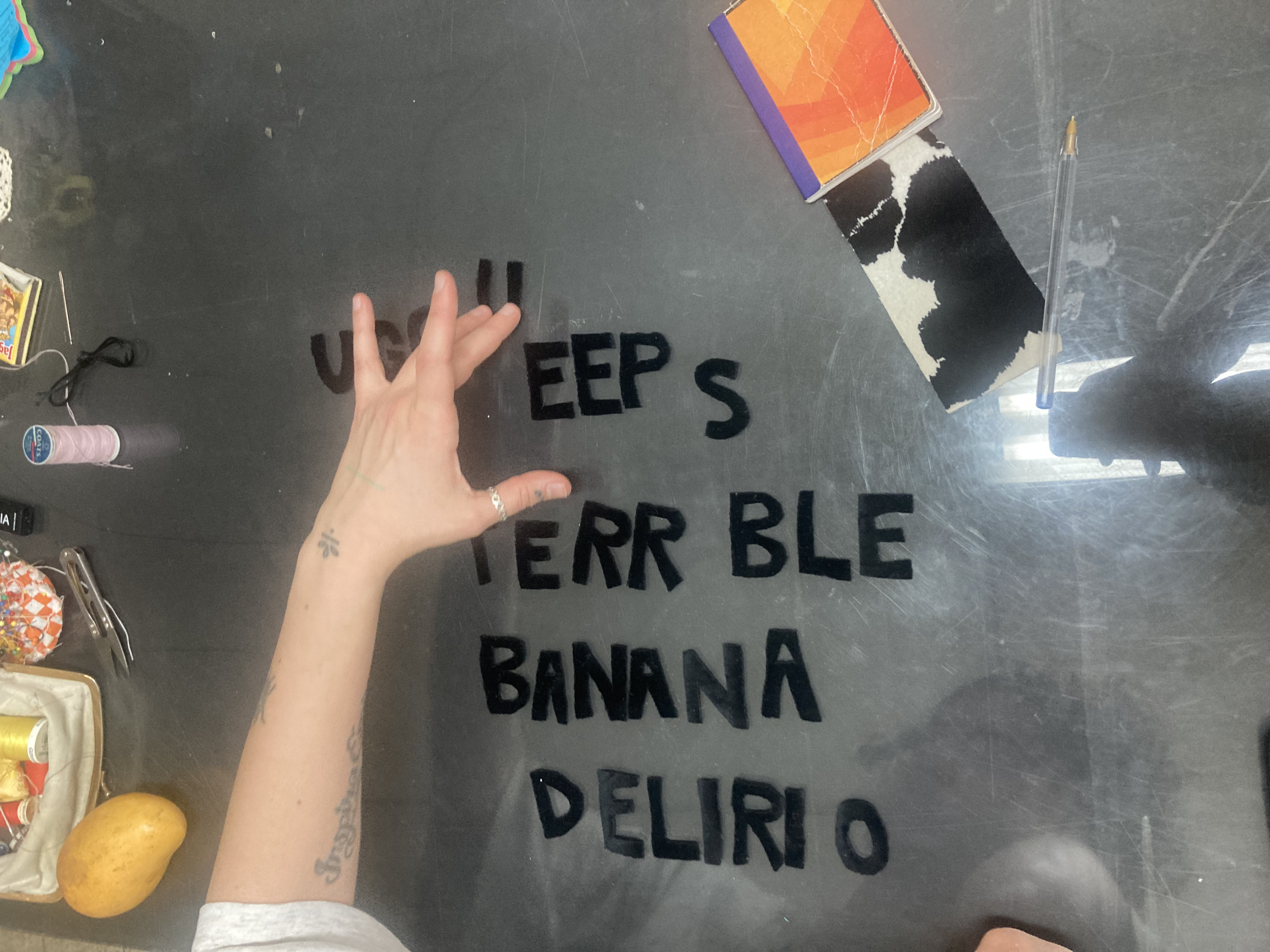

Photo taken by Ada NavarroMarch, 2022. This conversation happened in the studio of Chelsea Gelwarg, a US-American textile artist who has lived and worked in Mexico City since 2017. Pre-lunch with Chelsea: like poetry for clothing - grandma - almuerzo y más - friends are my artists / artists are my friends (!) - “normal” is?

︎︎︎

Her cloth-book project, Fuerza, was still fresh on my mind after seeing it at the Avant.Dev group show, Unidades Materiales. Presented as an open book on a pedestal in a brick-laden corner of the gallery space, viewers could turn the pages of the book, wearing cloth gloves provided by the artist.

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

︎︎︎

Addison : Where does voice come in for you? You have poetry in your work; does that installation extend into the performance space, into the spoken space?

Chelsea : The installation of the book and how I plan to install my next book is performative– exactly how you just explained it: the time that you have to spend with the piece. Putting on the gloves is an action so that you feel like you're part of the pages, right? You're covered in fabric. And that's why I'm interested in more, more fabric.

A : I like hearing about your relationship with fabric because it's multifaceted. You source fabric locally here in Mexico City but you also receive fabric from your family. There's antique fabric; there's heritage that’s being re-appropriated through these pieces that then come to light as tapestries and rugs, in clothes and books. Can you talk more about fabric?

C : I mean, my practice started, as it exists now, about six years ago, because I was such a high consumer. I had so many clothes. And I literally just started cutting them up to make new things. It started with like trying to make this “jean monster” Halloween costume, and then I turned it into like, one of my first signs, which then became this six year practice of dedicating myself to only using scraps and use materials and old clothes. So, collecting. Literally everybody has clothes in their closet that they don't want. It was so easy. So I've become more picky in the past years as the practice has evolved.

A : What do you look for in clothes now?

C : I'm always looking for texture. I go a lot to the pacas now and I'm always looking for silk and wool, which I can find in the five-peso piles. I always find it. And then collecting from friends or my grandmother who has given me so much material, so much material. She also works with textiles. She crochets more than anything now. But she used to work more with textiles, and just has boxes of things.

A : This family lineage with art in textiles always struck me as kind of unique in your case that you, your mom, and your grandmother have a couple of things in common. And you're not the only artist in your family. Although you might be maybe the most rebellious? Rebellious superficially, I don't know.

C : What do you mean by that?

A : Stylistically, perhaps? But I'm projecting. I don't know your family.

C : You're so funny. My grandmother is for sure an artist but I don't think she would ever or has ever really used that word. She's just like, I have to have something to do with my hands. I always have to have a project. That's who she is, but she's made like, 100 decoupaged chairs. She’s also someone that taught me about re-using materials. A lot of the furniture that she uses is stuff that she found in the junkyard and repurposed.

A : Did she teach you to sew?

Chelsea’s practice connects textile with text: Employing fabric as surface, device, and image, her work ranges from sewn compositions that function like paintings, to clothing, to cloth poems in ambitiously hand-woven fabric books.

C : In a way. Partly. No, I started sewing when I was 11 because my mom and I used to go into this quilting shop and the woman who managed the quilting shop came to my home after school and gave me sewing lessons. I actually still have this box of buttons that she gave me. I've literally had that for almost 20 years now. It’s in the corner right there.

︎︎︎

Chelsea in the studio with costume pieces from her collaboration with Lina _Bailón_ hanging on the wall behind her.

Chelsea in the studio with costume pieces from her collaboration with Lina _Bailón_ hanging on the wall behind her.C :You mean, how has the culture or the city influenced me? I don’t know about that question. I feel like you asked me that before… I feel like I’m… I’m just me here, I suppose. You know, I’m someone who always goes to the same places. I find the lunch spots that I like and I frequent, I know the people, we say hello to each other, I really get to know my neighborhoods. I love to know the street names and geography of a city. It’s super important and exciting to me… understanding the map [of Mexico City] I think that’s the thing that influences me, that’s what helps me feel at home in the center of one of the world’s biggest cities.

A : Are you thinking about stuff artistically right now that you haven't described yet or that you feel are bizarre thoughts, concerns or unrelated things that are coming up for you?

C : Shoot, I don't know. I've been thinking a lot about applying to residencies recently. I did one. I recently delved into the collaboration of costume work and choreography for this recital with Lina, which was a fascinating experience. My work is usually very solitary. I mean—not solitary. Like, I can sew around anyone and be in conversation while I'm working. But it's mine. So sharing that was, I think, an incredible experience and really important and difficult and interesting.

A : How did you do that? Navigate the collaboration and develop the idea together?

C : Lina came through with a really clear color palette: she wanted to work with flesh tones. And then it was a series of conversations. She also was really interested in having all of the orifices visible and highlighted while covering other parts of the body and came to me with the idea of being inspired by burlesque dancers. And then we went to the pacas together and picked up a bunch of fabrics, everything from the five-peso piles in the color palette that we created together. And then we just had a lot of conversations, and were here sewing together. I have more textile skills, right? She has more choreography. So I mean, I think it was really beautiful. It was difficult. It was interesting. It's definitely a meeting of egos. The end result was so satisfying, to be honest, and it was so inspiring for me—I want to keep making costumes. I've been thinking a lot and actually my application for this first residency, I applied with this idea of combining my loose page series and a nice idea of textile books with my knitwear and costume work. So I'm interested in making an outfit that includes embroidery patchwork, and knitwear that is wearable. But also a book you know, like legible fashion. Delicate, soft.

A : To me it seems to be that you do not discriminate your work as art or fashion.

C : All the fashion I make for me is part of my art. And it's part of my practice. Dude that’s so— I [recently] met this person who is an artist. Well known. Everyone loves his work, (and he’s ultimately a really cool person, I enjoy him) but when I first met him, he was like, really interested in seeing pictures of my work. I told him that I also make sweaters and knit clothing. And he was like, “Oh, I want to see but I only want to see it if it's not normal.” Like, me dio tanta risa pero whatever I was like, of course, the knitwear I make is not normal, knowing all of the history behind how I found this yarn. I make the patterns from scratch. I taught myself how to do all this, like—

A : The word “normal” is also just so nondescript.

C : But that's also really interesting, because the conversation around selling these sweaters later— people look at it as fashion. And people have a certain budget for fashion and they think about it differently than other people. But I took a month to make this sweater and I mean, and that's really interesting to me too. Because like, obviously, I make money because I have to participate in this world. And yes, I'm interested in putting a good price on the time and energy that I spent making something but I also want things to be accessible. He saw the sweaters and immediately was like “these are normal.”Not in person. He didn't see the sweaters in person. He didn't touch them. He didn't try it on. He didn't smell them, you know? But again I’m just like, you know nothing. I wasn't offended. I just was like, I am now discrediting all of your opinions.

A : Just talking about that language again, “normal,” that is very goofy to me.

C : It’s goofy! The piece is normal because It has two sleeves, a back and a front? Anything made by hand isn’t “normal.” People don't put time and energy into the normal.

A : Accounting for normal as an inherent negative.

C : Exactly, and I also don't want to do that to the word either. I hate negative, even positive connotations. I feel like you should be able to use language in a very expansive way. I mean, that's why we're poets.

︎︎︎

![]()

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

Chelsea napping in the studio.

Photo taken by Ada Navarro

Chelsea Gelwarg:

I am originally from New Jersey and I have been living and working in Mexico City since 2017. I have been sewing since I was 11 years old. I work entirely with used fabrics, donated by family and friends and collected at flea markets and discount bins. Each time fabrics are recycled or reused they are given a new narrative, a new opportunity to be experienced. I feel connected to the practice of quilting in this way, the saving and gathering of intimate fabrics and patching them together generates an archive of memory which I believe makes any piece I create into a book even if it doesn't take on the stereotypical form.

Follow Chelsea:

Instagram:@strips0ffabric

Website: https://chelseagelwarg.com

Addison Bale:

is a writer and artist from NYC. His work is viewable online: https://adi-bale.com

More from “Shedding”:

May 27, 2022

Emailing Emna Zghal

By Addison Bale

[Author’s note: It’s fitting that Emna Zghal and I held this over email.

Normally we sit in her Bushwick studio surrounded by paintings in progress while sharing a meal, discusings poems, reading, and considering the differences in the translations of poems that Emna had in two or three languages. Up until this point, we have never spoken through writing beyond the occasional text message. Here we talk about the cross-influences of writing and artistic practice, following a short chain of emails into candid territory. Disguised in other topics, Zghal’s paintings are actually the silent centerpoints of our conversation through which all other matters can be considered. We discuss poetry, language, the art world, capitalism; the themes that contour-trace this artist’s life and work. ]

Normally we sit in her Bushwick studio surrounded by paintings in progress while sharing a meal, discusings poems, reading, and considering the differences in the translations of poems that Emna had in two or three languages. Up until this point, we have never spoken through writing beyond the occasional text message. Here we talk about the cross-influences of writing and artistic practice, following a short chain of emails into candid territory. Disguised in other topics, Zghal’s paintings are actually the silent centerpoints of our conversation through which all other matters can be considered. We discuss poetry, language, the art world, capitalism; the themes that contour-trace this artist’s life and work. ]

︎︎︎

Addison Bale <sayhey.adi@gmail.com> Feb 13, 2022, 1:42 PM

to Emna

Emna,

Remember sharing poetry over lunches? It was a short-lived arrangement but you still managed to show me such beautiful work, reading segments from The Tree, by John Fowles, and translations of Borges. I have his poem you read to me, "Ars Poetica," saved in my notes and, if I remember correctly, you have that same poem pinned to your studio wall. Can you talk about your relationship to literature in your life and practice as a painter?

*

Addison

︎︎︎

Emna Zghal <[...]@emnazghal.com> Sun, Feb 13, 7:30 PM

to me

Poetry lunches were great! Literature has always been central to my understanding of art. My most cherished memory of my late father is him reciting poems on all occasions, mundane or solemn—at the dinner table, commenting on the news, or at family events. As a child, I didn’t always understand the words, but his delivery made me feel he was articulating the Truth. When I became an artist, these experiences of poetry remained the aesthetic standard that I aspired to. In my undergraduate years in the school of fine arts in Tunis, I was devouring all the artist monographs I could put my hands on but sought guidance as an artist from poets like Adonis.

Arte Poetica—translated as Ars Poetica—by Borges both validates the beauty of infinity and of being lost. Poetry is immortal and poor, he says. The poem is an antidote for our current culture, which has little appreciation for the lost and poor. I named one of my paintings Arte Poetica in 2008. I often circle back to Borges to reconnect with what is important, sincere, and free of hype. I have that poem pinned above my palette table.

The Tree by John Fowles is a book I bought at the New York Botanical Garden, and I read it three times in a row, because I found in it so much validation of my instinctive relationship with nature and creativity. It taught me so much, and still does, on how to articulate these thoughts. Our relationship with nature is mediated by this drive to name and classify everything, which passes for knowledge. Little is left for the personal and subjective experience one can have of a river or a flower, an experience difficult if not impossible to articulate with the clarity of science. I was intrigued when he mentioned that his novels come from nature, and how such a statement was dismissed by scholars who thought that only literary influences and theories of fiction and the rest of that intellectual midden, as Fowles put it, are valid keys into literature. How foolish! He spoke of the small and tidy garden of Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist who invented the Latin naming and classifying system of plants and much of nature, as the opposite of a shrine for nature lover and akin to a nuclear explosion whose radiations continue to pollute much of the globe. I find this a terrific and terrifying image to be true.

︎︎︎

Addison Bale <sayhey.adi@gmail.com> Feb 14, 2022, 10:43 AM

to Emna

Can I see your "Arte Poetica"?

I love that anecdote about your father. Such a beautiful legacy to have left that in your childhood.

Borges' take on the Ars poetica is so good for it's attention to fluidity and futility; that poetry returns like dawn and sunset daily, as though begging us to see it; that it opens and closes the day, and maybe, for being an expression of daylight, is what begets our consciousness. So Borges explains without explaining, or rather, his examination of poetry is one that opens it up to be the most common, almost unthinking presence and yet so crucial to be the day itself. Borges allows for that subjectivity that we tend to lose when art and nature enters the classifications of academia or the institution. And this is totally what John Fowles seems to be getting at when he writes about trees and nature! And is, actually, what you are getting at too when you talk about painting.

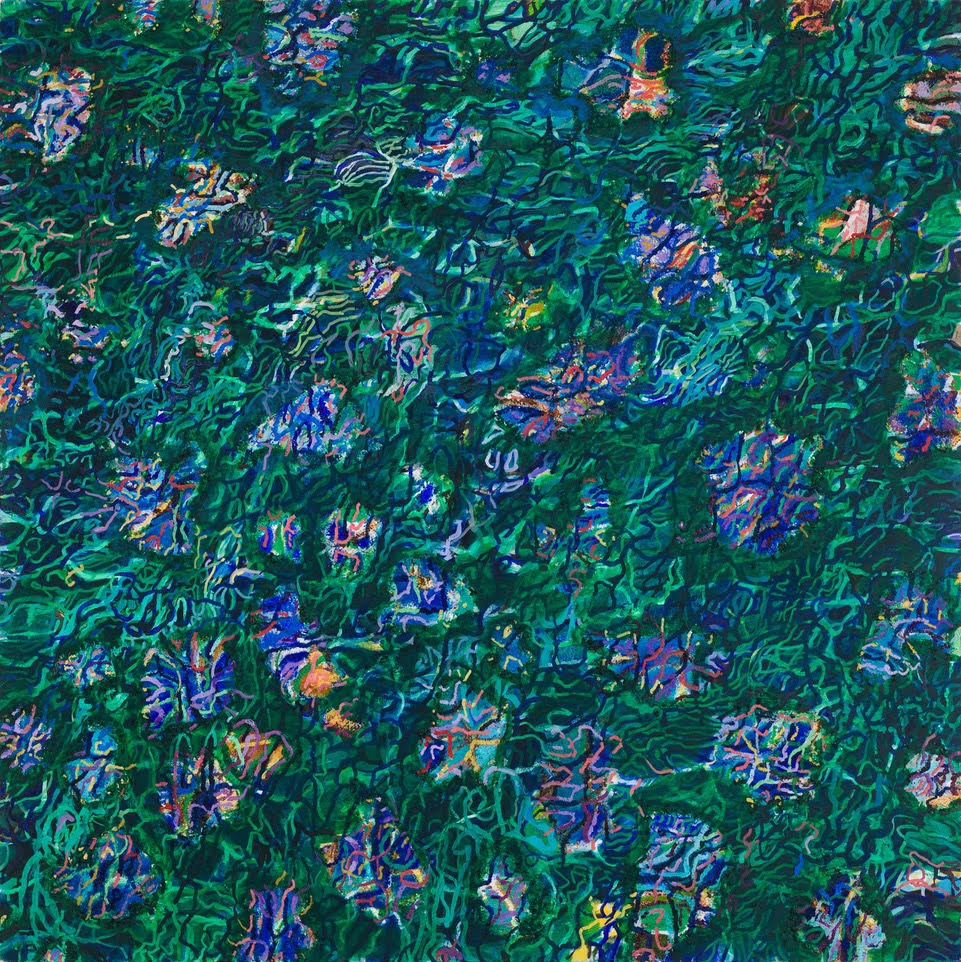

We've discussed before this overarching sentiment you reach for in art and life that you work within the unclassified and perhaps, unknowable phenomena around us, and that in doing so, there is the potential for much feeling and energy to interact with life through art. It seems that by clinging to the jargon of academia and the frameworks of art history, we relinquish so much of the intimacy between ourselves and art, whatever possibilities lie in that interaction. Your paintings, which are abstract but visually recall natural patterns (zoomed-out as in landscapes or zoomed-in as in shells or plumage) seem to be reaching for this conceptual experience of dwelling in the unknown in the myriad perceptions of pattern and randomness.

Do you see your paintings as images in dialogue with the literature in your life?

Are there ways that you are responding to your literary influences (including your father, including Adonis) somehow visually with paint?

︎︎︎

Emna Zghal <[...]@emnazghal.com> Tue, Feb 22, 10:25 AM

to me

Of course, here is my “Arte Poetica”.

It’s interesting what you brought up about the calcified frameworks of academia and the understanding of art and art history. Somehow the emotional experience of art seemed to have fallen by the wayside or relegated to an order inferior to concepts and art historical positioning. It’s as if that subjective experience of art (and similarly of nature) cannot be trusted, and therefore cannot be something that contributes to knowledge. I touched on this subject in my artist’s book Plato/Pineapple/Poetry/Painting. I see a parallel between Plato wanting to banish poets from his Ideal City (governed by reason) and contemporary art, which abandoned poetry as the language used to speak about art, in favor of theory (aka reason); and all that derived from that choice. All the talk of “subversiveness” does very little to actually undermine power. Many artists rail against capitalism, colonialism, and white supremacy; while little attention is paid to how nominally subversive conceptual art is very convenient for speculation. The making of art is outsourced to unnamed craftspeople or machines, and thus the possibility of failure is minimized and production maximized. The artist is now a brand and a studio CEO. It’s a far cry from being able to distinguish the hand of the master from that of the apprentice in yesteryears. What we lose, or lost, with this scheme is the sidelining of a whole realm of human intelligence. Being able to paint is a genuinely distinct form of human expression that is worth preserving, like dancing or playing musical instruments. Why should philosophizing crush all the rest? To the extent that painting survives, its validity is derived from an ideological content first and visual content second—if at all. Why would artists, critics, and art historians agree to this? I believe the answer lies in how intertwined the 1% is with influential institutions in the art world. Ready-mades are far more convenient for speculation. My ideas are heretical, not only because I was trained to paint and appreciate good paintings, but also thanks to the poetry that provides an anchor for me outside of the visual art world. Poetry emboldens me to operate with a different set of values.

In that sense, and to go back to your question, I don’t see my work as a response to literature. Poetry, and literature in general, schooled me in a certain form of knowledge that is not necessarily averse to reason, but one that fully embraces the full scope of experiences, beyond just what we can rationalize. I remember a quote by Adonis I had on my wall when I was an undergraduate student in Tunis: “Sufism as a method of knowledge.” He refers to the mystical poets of Islam. It struck me then and challenged my views on religion. Yet, seen through that angle, I understood what religion, as a form of human thought, had to offer us. Arguably some of the best music, architecture, or painting came from religious traditions. Poetry is different, the most important Arab poets, like Al Ma’ari and Al Mutanabi, were not religious. I say this because I think that poetry is also a method of knowledge. What I learn from poetry, and literature in general, is that personal experience and feelings anchor me in truth and artistic authority stems from a distinguished personal voice, ideals that the visual arts seem to have abandoned. I quote Ann Temkin, MOMA’s Chief Curator for Painting and Sculpture in my book Plato/Pineapple/Poetry/Painting: “Contemporary artists disavow transcendent goals of truth and beauty.” I think she’s right in her observation, yet I refuse to operate within that paradigm.

︎︎︎

Addison Bale <sayhey.adi@gmail.com> Mon, Feb 28, 2022, 1:03 PM

to Emna

To your point, the tentacles of capital and market-influences operate differently between the fine arts and literature. Speaking for poetry specifically, there is simply much less money involved and therefore much less money at stake in the world of poetry. Compared to the art market, poetry is still an artform relegated mostly to basement bars and living-room readings. Though perceptions of poetry are shifting with this generation, with social media and the work of new poets, it remains less commodified (compared to fine artworks) and therefore its value is always going to be fixed to the standard of a small book. I have often felt that this is actually a good thing for the art of writing, which is largely so exempt from the possibility, however faint, of explosive wealth. Though making money as an artist may be insecure, there is still the specter of prospect and value: paintings are worth x amount of hundreds or thousands. On the contrary, a single poem has no dollar value and its value in a collection is exactly the same on every platform, every mode of download or hard copy—as long as the poem can be read its value is immortal. So as an arbiter of truth, poetry seems to defy (slightly, and not to ignore its own trends and the machine of publishing houses) the erosion of "truth and beauty" through capital...I say this hesitantly though, still thinking as I type.

What is it that we do then? as painters that live by day-jobs, painters that mostly paint in obscurity, hustling for opportunities but likewise wary of the world we tempt to be more deeply involved with?

I consider your work as unique for its unwavering vision and persistence to pursue a practice that explores abstract painting as a reflection of or maybe distillation of the natural world, the imagery of the natural world and the information you take from it—so by painting and continuing to paint against market trends, who are you painting for? Is your practice solitary? Do you paint with a wish against capital? How do we exist as artists and work around that very art market you describe? Is it just a matter of gritting teeth and carrying on?

︎︎︎

Emna Zghal <[...]@emnazghal.com> Sun, Mar 6, 7:45 PM

to me

So many interesting questions there. Let me answer the straightforward ones first. Is my practice solitary? Yes, on some level. Sure. Solitude is crucial for me to achieve any depth. I mix with very few people to shield myself from the uninspiring. To get to your other question, who do I paint for? I am seeking an audience that shares similar values. I believe they are out there. This interview is part of an effort to reach out. I can’t paint on the desert island. What’s the point of self-expression if I’m not communicating with anybody? Looking back at the years when I stopped showing my work, I was blasé. I felt that this purportedly postmodern and diverse artworld had no tolerance for what I wanted to do. I was not ready to toe the line expected from “the native woman” and dish out cheap exoticism and victimhood stories. I felt beat up. I had no support, and still don’t, in my stubborn pursuit of this sort of abstraction. Yet! Yet here I am at it again. I gathered some strength, and I feel like I can take some punches again without being entirely knocked down. I sorted out my immigration status, and I have a day job that allows me to be in the studio. It’s far from ideal, but it’s a workable situation.

Do I paint against capital? No, that makes no sense. I steer clear from preposterous trendy and heroic claims of the sort. I do have a critical view of capitalism and how it functions in the artworld; and most importantly how it seeps through the mentality of art professionals: curators, art teachers, and artists. Books like “Privatising Culture” by Chin-TaoWu, “El Fraude del Arte Contemporáneo” by Avelina Lesper, and “La bêtise s’améliore” by Belinda Cannone are inspiring and empowering writings on this matter. Contemporary art posturing against capitalism is just that, posturing. The validity of a given work of visual art is no longer derived from careful visual examination, rather from statements, biography, and, above all, from market value. It’s lamentable that we, the art professionals, ceded our visual ground to literally stated ideas.

The allure of rebellion and subversiveness is superficial enough as to not threaten any established order. There’s no outrageous art Banksy can do that doesn’t feed the speculation frenzy of his work, or otherwise leads to a concrete social change. It’s important to be lucid about that. When truth is abandoned, the difference between saying and being no longer matters. There’s a classical Arab song that goes like this: Not all who tasted love, know what love is/ not all who drank wine are wine connoisseurs/ not all who sought happiness found it/ and not all who read the book, understand it. Truth matters to me, and so does discernment. I do believe nevertheless that making art and understanding it outside a framework of efficiency, purposefulness, and fame is a step towards lifting the limits put on imagining an alternative value system. That’s the value of being anchored in poetry, because, and as my friend Ammiel Alcalay says, poetry largely escapes capitalism. It’s not purposeful and efficient, it’s imaginative.

To go back to John Fowles and his critique of Linnaeus, it is legitimate to observe that the careful detached taxonomy of nature created all but an illusion of knowledge. Clearly, we’re hitting a wall. Knowing without humility and respect before the examined subject—in this case nature— is leading us on the path of self-destruction. Had we not sidelined emotions in the way we did, perhaps we would have been on a different path.

How do we carry on in these conditions? I didn’t know how to go on for a while. Without ever thinking it could happen, I strayed from the artworld. I got into Argentine tango, and it was like falling into a hole. I applied myself to learn an art form I had no natural abilities in, and at the end, I learned way more than dance steps. Tango taught me anew how to value craft, communication, disciplined practice, and preserving a tradition while being creative.

Now I feel I have a clearer vision of what I want to pursue. How to be a more poignant painter. In my case, the criteria is how to create images as mesmerizing and captivating as nature and its forms: vast landscapes or small shells; while bringing the viewer somewhere unknown and imagined. Being a better painter is more fulfilling an ambition than chasing the next clever idea. It’s not just gritting your teeth and keep on going; it is that of course, but also striving to stand on ever firmer ground intellectually to carry on. The gatekeepers might operate with different values, but you can tempt them to embrace yours. It is a worthwhile pursuit.

︎︎︎

Follow Emna:

Web: www.emnazghal.com

Instagram: @ezghalart

Emna Zghal:

Emna Zghal is a Brooklyn-based visual artist. She was trained in both Tunisia and the United States and has shown her work in both countries and beyond. Reviews of her exhibits appeared on the pages of the New Yorker Magazine, The New York Times, Artform amongst other publications. Noted public collections include Newark Museum, Flint Institute of Art, Yale University Library, The New York Public Library, The Museum for African Art, NY, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NY. She has received fellowships, prizes, grants, and residencies from: Creative Capital, The MacDowell Colony, Women’s Studio Workshop, American Academy of Arts and Letters, Cité Internationale des Arts (Paris) and others.Addison Bale:

is a writer and artist from NYC. His work is viewable online: https://adi-bale.com

More from “Shedding”:

February 25, 2022

Kiko’s Practice One Year Later

By ADDISON BALEIn conversation with Kiko Bordeos

[Author’s note:]

[On January 8th, 2021, my first segment for The Quarterless Review, “Kiko’s Jeepneys,” was published online. The article was a narrative account of my first conversations with Filipino painter, Kiko Bordeos, emphasizing his daily practice and the influences from life in the Philippines visible in his paintings.

This article is a year’s long follow-up recorded as a dialogue between Kiko and I in late autumn. One year later, this conversation locates us, two painters who were strangers to each other not so long ago, as friends. As I type these words, Kiko is only a few feet away from me painting against our shared wallspace in the Knickerbocker studio where you can find us on most nights of the week painting side-by-side.]

The Smiths are playing in the background.

Here we are in the studio looking at Kiko’s works in progress…

︎︎︎

Detail image of “Dark Entries/Love Dormancy”

Addison: …you’re almost always looking at your work and then you never go more than 5 minutes without touching something on the surface. The image builds up.

Kiko: It’s definitely getting dense.

A: The density in this piece acts like a surrogate for speed.

K: It's very much like New York City.

A: Tell me more about these paintings. What's going on here?

K: I’m working on some foreground and background action. The background becomes a fun place to juxtapose minimal templates with lines and movements of colors. These simple plays are what I like about minimal art, you know, like Carmen Herrera. Right now I'm not really focused on clarity in my work. Maybe having a studio is what makes me want to go like, boom, boom, boom, boom. There's no story in it. These paintings are visual distortions; maybe, visual sonic booms, visual cacophony.

A: Do you think about specific things when you're working? Is your head noisey when you paint?

K: Not really. Recently I’ve just been looking at a lot of artists that I like, thinking about their work. Some of what I’m doing with paint is like a nod to them, homages to them. But I don't want to name names.

︎

8:01K: Line and circle: for me being bilingual with English and Tagalog— I’m more fluid with Tagalog. I associate it with lines because I am more comfortable composing a painting through lines. I can’t really work with circles, so I think about them like my English. I began to think about how I enunciate words in English, which takes effort. It’s kind of like how I play with circles, introducing circles into the linear compositions. I don’t think I could make a whole painting of just circles.

A: You’ve never mentioned this before.

K: Never mentioned what, bilingual?

A: I know you're bilingual, but you've never made that explicit connection between English/Tagalog and line/circle which function as the basic elements of juxtaposition in your recent work.

K: Well, maybe it’s more subconscious really, because I want to explore other shapes but I feel like right now I can’t let go of lines and circles. But, I don’t know, maybe in a year or two I’ll be doing landscapes and going on trips upstate, expanding my shapes. [laughing]

A: Do you ever consider your paintings symbolic? Are these shapes filled with the symbolism of an idea or the idea?

K: Not really. I haven’t really thought about it, so not really. I usually just say: it's anxiety. Just make it crazy, sexy, cool. [laughing] I just make humor about it, about painting.

A: [laughing] It’s not easy to put words to your work, especially when it comes to abstract art. Do you know what you're gonna call these paintings?

K: This one is “Dark Entries/Love Dormancy.” I got it from a song. Oh, Bauhaus. I'll send you the song later. In therapy I’ve been talking about dormancy; dormancy when having to move through the changes like Fall becoming Winter…and then love is just such a complex word.

A: I love that love can be used for pretty much anything in English. I love you, romantically. I love pizza.

K: I love pizza. It can be so casual but when you want to say it to that person then it becomes hard.

A: What’s it like in tagalog?

K: Mahal.

A: And you can say it for a love of things?

K: Yeah. In Tagalog, when you say mahal kita it means I love you, but mahal also means expensive. Like, look at this expensive chair. Mahal kita…Yeah. So there's that duality you know. Layers. If you’re gonna say to someone in English I really love you, in Tagalog, you have to repeat. There’s a lot of repetition in the language. If you're gonna say, I really love you to someone, you got to say, Mahal na mahal kita. There’s that repetition.

Just like this duality between Tagalog and English, line and circle, I’m interested in these values of love. How easy, unimportant it is, but then it has this emotional weight that is so intense when you are in love. I feel like you can relate to that.

A: I recently said I love you to somebody and they said it back. It was our first time saying it to each other.

K: I remember, didn’t you say it by accident at first? You were talking about plants?

A: [laughing] Yeah. My partner and I were watering my plants, and my plants have these long names, and I was like, wait I forgot their names now! I was talking to Xin-rui and I was like, wait wait wait—shoot what’s this one’s name again? And she goes, ILoveYou, and I was like, oh right ILoveYou. [laughing] The plant is named ILoveYou.

K: [laughing] Being bilingual, I'm interested in the philosophical mocking of words sometimes—mahal kita—these sounds attached to meanings we make up and agree on and how these sounds can build up so much emotional force over time. Yeah. Like, I would tell you who you are, you know, someone like, Oh, I love you guys. And I love this. That was, but if you're like, you know, that line of being like, romantically, seeing someone or just like, you know, it's just hard. Emotional weight.

︎

A: I remember talking to you a year ago, and you also explained a little bit about how emotions come through in your painting. How you remember emotions or periods of time when you look at your work, the work takes you back to how you were when you made it. Talking to you has made me ask myself, what form do my emotions take on the canvas, what colors do they come in, What imagery conveys emotion, for me. Do you feel like you have struck the visual language that you need to depict emotions?

K: Yes and no. Words don't come easily for me and this imagery doesn't come easy either. I have this painting in my head. I used to sketch a lot but I stopped because I just don't have time for it. Maybe if I don't have a 9-to-5 job I'll be sitting for like two hours and sketching stuff. But every time I do that, then I create final paintings that become different from the sketches.

So I paint by being in the moment and if there’s feelings involved then maybe I'm kind of aware. But I probably see it more later. It’s a visual cacophony during and after. Did I answer your question?

A: If you had to identify or just pick a shape that corresponds to the feeling of doubt. What does that look like?

K: Doubt?

A: Yeah.

K: Wow. What is that? That's amazing. Probably a half circle and a line interrupting it.

A: Wow.

K: You never see a half circle around. Yeah, probably a half circle and then a slash of line.

A: Maybe you look up sometime and see a half moon and a plane with a chemtrail bisecting.

︎

21:54

K: I didn’t use any red for this painting because I alway associate red with anger and violence. So no red for this guy who's a happy one. I have one painting that is 8-by-10 [inches], from the early days of therapy and dealing with anger and stuff like that. I’ll just show it to you. Do you want a visual right now? Because I feel like I show it to my friends and my friends are like shit. This is kind of violent for me.

“Seeing Red” Acrylic on panel, 2020

A: Oh, dude, I love this.

K: But every time I look at it now it’s just like a timestamp of what I was in the moment. It’s May, 2018. I think it was the first two months of being in therapy. Therapy is awesome by the way. Shout out to my therapist. [laughing] We talk about painting in therapy a little bit. She used to be a social worker and she deals with a lot of, like, creative people, also immigrants, people of color, so I feel like it's perfect that I fit in that category.

A: I'm really attracted to the earth tones in [“Dark Entries/Love Dormancy”].

K: The browns… I like how it like blends with the teal blue there. I've been trying to work with a lot mars yellow, yellow oxide, and.. Yeah I love yellow. Wiz Khalifa “Black and Yellow.” [laughing]

30:01

K: Three favorite yellows: diarylide yellow, hansa yellow opaque and dark cadmium yellow.

35:13

K: I can't help myself– [gets up to paint] Talk.

A: So what are you doing right now in this piece?

K: I'm just trying to add some more movements. I’m painting in angles that rival one another to create that tension for your energy— I’m thinking of sonic energy. That visual cacophony.

A: Do you consider your work illusionary, as in Op Art?

K: In a way. But I’m interested in the illusions of external forces and influences in my work– not really painting in that way though, playing with your eyes. The world does that work for you, like, you go out on Knickerbocker in 1990 and there's too much shit going on. You hear trucks, you hear people yelling, talking, cars, bicycles. So I feel like my visual references represent this environment; representing street noise, street energy. I don't know what my art would look like if I lived upstate. I’d probably become like Bob Ross. The Joy of Painting!

︎

44:20

K: I relate to your work because you depict windows. Some of my work from Prospect Heights was looking at windows, very influenced by Jonathan Lasker and Peter Halley.

A: I love windows. I love doorways. Love windows and doorways the most. I like hallways too. I keep coming back to those frames that act as gateways between the private and public hunan. I like the simultaneous transparency & opacity these gateways offer: a door opening/closing.

46:14

K: Do you try to look for a lot of symbolism?

A: I try to some degree. Then I try not to. Honestly, putting it like that, as straightforward as that is the first time that's ever come out of my mouth. When it comes to my own work. I'm aware of what I'm interested in but I can't engineer symbolism. What does it mean? It’s a painting, I don’t know. But this creates an issue for me as well. I reckon with other people’s theses through painting and still yearn to say something but time and again I know the best work comes as a great surprise against my initial intentions. I accept that the work will develop beyond my initial conception and hopefully, it surprises me.

K: Yeah. Surprise is good and sometimes it is like, wow, that’s good, and then again, it can be disturbing for being so far from your expectations. I like sitting around and just like carefully being thoughtful about what to do in the painting.

A: Me too. I'm just looking most of the time.

K: And you know it’s also about getting away from the painting, getting out of the studio, doing normal things, going to the gym or the grocery. It's all part of it.

A: Everything bleeds into it.

Completed work: “Dark Entries/Love Dormancy,” 2021. Acrylic on canvas.

Kiko Bordeos:

Kiko’s work can be followed on Instagram @kikobordeos where he also makes direct sales for interested collectors.Kiko has at times dedicated the sales from his work to Bushwick Ayuda Mutua and we would like to share that for anybody also interested in donating or volunteering with them: https://bushwickayudamutua.com

Addison Bale:

is a writer and artist from NYC. His work is viewable online: https://adi-bale.com

More from “Shedding”:

August 22, 2021

Sculptural Autopsies with Yasue Maetake

[Pt. 1]

By Addison Bale

[ Author’s note: This text traces month’s of correspondence and time spent with sculptor Yasue Maetake. To reflect the diverse nature of our communication, this article has been hewn out of email exchanges, journal entries, notes, observations, and some recorded content. The linear sequence of the writing is unimportant: any lines and paragraphs can be read variably, theoretically in or out of context, mismatched and replaced with lines from other sections. The only important thing to know is that my words as the author are non-italicized. I use italics when quoting Yasue’s words or emails, when quoting her husband, David, and for word or concept definitions. I use italics as opposed to quotation marks for Yasue’s words because most of the time I am not actually quoting her, but interpreting and restating. ]

︎︎︎

A broken-down car, palette-fulls of Benjamin Moore paints, scrap metal, spare ladders, rolling shelf units, panes of glass, a charbroil grill, green True Value bins, aluminum rods, a blue steel rolling staircase, chassis, wood palettes, filing cabinets, planters, spare fuel tanks, rust-covered wheelbarrows, wagons, trollies, a forklift, crutches and a walker, trash cans, piping, milk crates, tarps, foam core, shopping carts, folding table, scrapwood, 2-by-4s, etc, all sit in the lot behind Platz Hardware True Value where Yasue also keeps her studio.

︎

Email from Yasue:

Hi Addison, you are welcome to stop by my studio anytime. Whether during the week w/o Ai or weekends w/ Ai. I am also fully starting to focus on the studio. For you to observe my real life, how messy and horrible practice, it might be interesting to look at. All past publications embellished my studio practice with cool material engagement, with cool pants with artistic paint marks on it but the reality is really more depressing and miserable being covered by dust than you think. Also, on weekends, I am mad and yelling at Ai while she is climbing 12 feet high scaffolding and tries sneaking to drive a forklift (seriously. she learned by watching David) so, there is no "cool picture" of artists meditating on their practice or a "smiling mother."

Just letting you know for your head-up!

︎

Now I wanna kick myself for not having recorded more of our conversations. I feel like Francis Bacon painting people from memory and soiled photos towards an image of his own devices (often beautiful, often monstrous). I am scanning my notes and re-membering the things Yasue and I have done and discussed over the past few months of correspondence.

︎

Politics, for one. Do you consider your work political?

I say, “No,” but this is partly because I know that it is not received that way.

︎

Day with Yasue and Ai-chan ~ May 1st, 2021. From my journal:

Met at Myrtle-Wyckoff. Ai-chan eating a hotdog. We go to Printed Matter photo show on St. Marks place to see Gryphon (Rue), who is curating/founding D R O N E gallery at Hudson & Chambers St. Stopped at Sunrise Mart & Yasue bought a week’s worth of groceries; Ai-chan nonstop singing/complaining and creating diversions by talking to strangers everywhere we go.

Back on the subway, Ai-chan fake-crying.

Out of the subway, eating umeboshi & onigiri & curry pan & pocky in front of D R O N E, talking about family & poetry. Ai running around, entertaining a woman who is eating a salad.

Inside the new gallery space, Yasue checks to see if this chunk of exposed copper pipe in the cement floor could be used as a conductor for something…Ai-chan & I have moments of calm as she rests on a white pedestal & drinks Yakulte. I ask what she thinks about her Mamma’s art & she gives me a thumbs up. At the same time, artist Viktor (Timofeev) is in the process of muraling on the back wall of the gallery with water-based pastel, hand-painting/smudging them on.

Then → → → → walk across Chambers St over to Chinatown, stopping in playground for Ai-chan to play for a bit, then carrying Aichan all the way to galleries. First, M23 gallery, where a minor incident occurs: Ai-chan taps a resin-brick sculpture with her tiny foot, Yasue goes to re-adjust bricks, the gallery assistant screams at them, sharply and loudly and I am startled from across the room:

“Don’t touch it! Do you know how much that costs?? I am shaking!!!”

Ai-chan scared; Yasue, a sculptor, knows that resin is not fragile…

Then ATM Gallery: artist Kyoko Hamaguchi’s minimal houses of colored threads suspended in hand sanitizer dispensers. Ai-chan chats with gallery owner and people on the street. A cute puppy embraces Ai-chan. Yasue and I enjoy talking to Kyoko—then time to go!

Ai-chan cries, says she is tired and wants Mamma to carry so I take the grocery bags and Yasue takes Ai-chan and I walk them to the subway, promptly realize I have lost my wallet.

︎

Addison, maybe you can briefly explain: Chan (ちゃん) expresses that the speaker finds a person endearing. In general, -chan is used for the names of young children, close friends, and babies. It may also be used for cute animals and lovers.

︎

Notes after D R O N E show, “The Location of Serenity” :

Without a photo reference, I recall Yasue’s sculpture like a reaper, like a harpy, like an open heart with long stents, the stilted legs of Dali’s hungry elephants, bag-like and ribbed against a cloudless blood sky—the piece is larger than a person, except maybe an NBA player, though it assumes an airy, almost avian posture echoed in some of her smaller works. Unlike Yasue’s more recent sculptures, “Ascending Industrial Bouquets,” is not made up of animal bones or seashells. Very skeletal nonetheless. This I remember. It is an anemic couplet of steel, brass, and copper with one semi-glossy shock of resin at the waist, and a second, stooped burst of resin suspended at the peak. Baby resin and Mamma resin. Somehow, a composite of materials found and manipulated still draws out the soul of something.

︎

Am I interested in owning the artwork? No, I told you. I don’t like to have the work around me. The urge ends in the studio. This urge—that is the urge to make, is unconditional and a bit scary—logically I can explain my other responsibilities, but the urge to make things is distinct and probably inexplicable, but nobody asks about this.

What do people ask you about?

Normally, they ask me how I got the camel bones. Then they ask me how much they cost.

Is it possible to understand the motivation that provokes you to make sculptures?

I should write down my thoughts during my process because something very close to the answers for my own process pass through my mind but then I forget. It’s all very elusive, come and go, come and go, so I fully rely on this elusive, ephemeral image. When I nail down this almost-there-form, it is about trapping and archiving it instinctively. Everyday I am thinking about these things.

︎

Seashells from the beach. Some bones too (camel). Most bones sourced from a taxidermist, some found. Many materials found or given. A neighbor is removing tons of bamboo overgrowth from their yard, so Yasue takes it. I show up at her studio in a moment when she is cutting and curving and grinding down rattan (similar to bamboo but different) as an echo of her other recent materials acquisition: old trumpets and trombones from a hoarder on Craigslist.

︎

I am back at Yasue’s studio, sitting between a rolling steel staircase and some rusting filing cabinets in the back of Platz Hardware True Value, her husband David’s store. We are talking about many things and then David comes out to say something—I take the opportunity to ask him about Platz:

How did you get involved with Platz in the beginning?

David: They were gonna shut it down, so my brother and I decided to buy. Because the Depots were coming to New York, all the old hardware stores were shutting down. Gottlieb’s, Harry’s—and I’ve been coming here since I was Ai’s age. You see one of my eyebrows, see this scar? That’s from this store when I was 4. If one more hardware store closes in New York, then we are the oldest continuously running hardware store in the city.

How long have you had the store now?

D: 21 years. Almost 22.

Yasue: Yes, so finally cleaning the junk out.

D: You know all those little comments that you try to stick in there, it’s not necessary.

[laughing]

Y: But do you know a lot of idiot art-folk think that this mess is an inspiration of mine!

D: No—I’m an artist also and this is my creation [gesturing to the variable heaps of refuse and backstock piled up in the ass-end of Platz.]

Y: Actually, David is good. He has a very good formal sensibility. Better than many artists. He has good eyes and is good with materials. And physics.

︎

Ai-chan stumbles over with Yasue’s phone in her hand, singing along to something, then singing loud enough to drown out the conversation. An ice cream truck jingles down the block. Yasue, referring to Ai-chan, says, She knows the vibe! Now we have more critical talk so she sings and distracts. She’s mean.

What is transmutation for you? Is it for us to see the unification of materials through form? Is it about the inanimate becoming free standing? Or brass sharing a leg with bones and bone sharing an arm with glass and glass sharing a spine with seashell…

Unification is certainly an interest of mine but not as an end goal. I view unification as a part of the transitional process of the materials and then we keep going—there is no stopping at unity. Transformation, changing—yes, changing—but after changing, I do not declare the finished product. It is about ever-changing, ever-evolving; continuity where I might have anticipated a conclusion or a logical terminus. For me, none of the sculptures are at their end, per se. The end remains arbitrary, even as I accept the end of labor. Movement and dynamics are how I see everything—this is how I view the world of substance.

Realistically, I am using stone, concrete, animal bone, and metal—these impenetrable hard substances, but my worldview, at least metaphorically if not also metaphysically, is that the distinctions between vapor, liquid, solid, are all unified by the same atomic units, and therefore, their barriers are always, on some level, psychologically imposed. I impose my perception of the world through the image of the sculpture. In looking, viewers can sense this fluid, transforming, dynamic materiality.

Ironically, you perceive the world through permeable distinctions, and yet you understand better than most people the actual compositional qualities that make every material unique. You know from experience what it’s like to cut through bone vs. steel, for example.

Yes, well I deal with the reality of these hard forms but live in a fantasy of transmutation, which is what the show is about.

︎

Continuity; not just abrupt optimism, but the aspirational journey at the confluence of tune, arriving and re-arriving at beginnings which are naturally optimistic. To begin again is in some way to always repeat. To either doom oneself to repetition or open oneself up to the permutations. The inanimate materials throw out some suggestions to the sculptor, Yasue, throughout the process: save me, assemble me, cut me, smooth me, grind me, melt me, weld me, glue me, fix me, break me, burn me, polish me, splice me, hoist me, name me, repeat me, etc. Brass plumbing rods become korean chopsticks become the bones of wings hinged to the grooves of actual bones, etc.

︎

Politics are undeniably present, always, somehow, but some people speak louder than others. People do not look for political angle in my sculptures; they look at my work and assess whether it is utilitarian or not, decorative or not. They tend to isolate the identifiable features in the sculpture and then they want to know, how much do camel bones cost? Where did I find them? And these stones, and these metals—where to find and how much?

︎

Addison, can you write a brief sentence about this sculpture?

I want to quote and introduce you by saying : "My fellow Addison Bale told me "This piece is blablablbal XXXXXXXXXXXXX" that I really appreciate. Now we are working on some creative writing project together. etc etc....."

︎

“Ascending Industrial Bouquets”: Grim reaper of brass bones and harpy’s wings: a sour-patch polymer with secret soul and it’s stalwart mother with the metal hood. (Baby resin and Mamma resin!)

︎

Another Japanese sculptor suggested that Americans focus on the material components of a sculpture over form/balance because there are no earthquakes here. Form is taken for granted. Precarity is little more than thematic. In Japan, form is the essential question at the heart of sculpture.

(Yasue’s skinny-legged sculpture, “Ascending Industrial Bouquets,” for example, might not survive in Japan!)

︎

Symbolism key to Yasue’s most used materials, according to the author:

Bone = beastial death (though since it is repurposed, it is either under examination or given a symbolic new life. Therefore, bone simultaneously represents autopsy, medical science, truth, and reincarnation.) Seashells = mathematics, repetition, whimsy, ancient history, and overfishing. Metal of any kind = human genius, hardness, softness, irony, cyborgs, and most importantly, the future. Stone of any kind = western fetishism, monotheism, and obesity. Paper = weather systems, fruit, and the Edo Period. Plant matter = motherhood, neighborliness, and non-judgement. Resin = regret, remorse, and retrograde.

︎

Even though I poetically claim to not see the boundaries between materials and states of vapor liquid, and solid, it is true that on the molecular level there is in fact no boundary. Sound is included in this.

Follow Yasue:

Web: www.yasuemaetake.com

Instagram: @yasuemaetake

Yasue Maetake:

Yasue Maetake is a Toyko-born artist living and working in New York. Using

a wide variety of influences, her sculpture evokes associations with

Baroque Dynamism and Animism, along with futuristic variations of

natural forms and industrial aesthetics. They partner directly with

human customs and technology.Addison Bale:

is a writer and artist from NYC. His work is viewable online: https://adi-bale.com

More from “Shedding”:

November 16, 2021

Sculptural Autopsies with Yasue Maetake

[Pt. 2]

By Addison Bale

Yasue outside NADAx Foreland in Catskill, NY. Photo taken by Matt Austin.

[Author’s note: An important thing to note is that my words as the author are non-italicized. I use italics when quoting Yasue’s words or emails and for word or concept definitions. I use italics as opposed to quotation marks for Yasue’s words because most of the time, I am not actually quoting her, but interpreting and restating. ]

︎︎︎

Addison, can you edit the below?

The truth is, I wanted to go to Japan for my upcoming show, but I found I couldn't, so I decided to invite my parents to come spend two months here this summer. During their stay, I have felt like I'm standing around like an idiot, moving at my middle-age speed like a turtle, facing a child and elderly parents whose company is like time-lapse video/film/montage? Passing in front of me—my daughter perhaps became 2 inches taller and I noticed that my parents needed more naps.

And I questioned, what I was doing?

︎

The weekend of August 28, 2021, we went upstate to the town of Catskill, NY, to see Yasue’s sculpture in NADA x Foreland. Her piece, Mass Inception, was well-positioned on the top floor of the exhibition illuminated by a corner of daylight pouring in from the south- and west-facing windows. Yasue introduced me to her gallerists, Elle Burchill and Andrea Monti of Microscope. We gave them a riso-printed copy of our article, Sculptural Autopsies with Yasue Maetake Pt.1. Yasue got to work, talking, moving around with people. I cruised the galleries, latching on and off to acquaintances for an hour or so before assuming a wallflower's posture at the edge of the room, performing intrigue while idling between the sculptures, arranging myself in relation to Yasue’s position, close by without obviously hovering.

We took several coffee breaks. Just outside the fair at HiLo café, our friend Daniel Giordano had two gross and gorgeous sculptures dominating the window display. Ai-chan, who just learned to use the phone, was calling Yasue repeatedly.

Back inside the exhibit, Yasue was spinning Mass Inception, trying to decide on it’s best angle in relation to the light coming through the windows. Microscope’s Elle and Andrea assisted the process of angling. I resumed my position by the window, pretending to write stuff down in my notebook.

Later, we found surprisingly yummy Thai food on Main Street and Yasue dealt with Instagram, then fielded some very basic questions from me about sculpture. What do you think of the Pietà? What do you think of Richard Serra’s work? Isamu Noguchi?

I know I shouldn’t say it but when I think about any art of the old masters, I feel contemporary sculpture is often embarrassing... Myself included… Richard Serra and Anselm Keifer are influences for sure… Noguchi, perhaps… but the best of all is Toya Shigeo...

Yasue Maetake, “Mass Inception,” 2021. Terracotta, epoxy, polyurethane, coated styrofoam, synthetic paint, steel, marble, resin, natural soil, found bird’s feather. 45 x 43 x 41 inches. Photo taken by Matt Austin; courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery, New York.

︎

It’s just such a waste— $300 dollars for one night in Catskill? I mean, there is not even space for two people! But it’s my mistake. I misunderstand the pricing— it’s just such a waste.

The Airbnb listing was misleading. You showed me the photos— I also expected at least a bedroom separate from the kitchen.

It doesn’t matter what the situation; $300 for me to come one night to Catskill, a day I don’t take Ai-chan to gymnastics or be with her, be at home preparing for my new class’s syllabus tomorrow. I just feel it is a bit embarrassing, this being-an-artist thing sometimes. Why should this be a priority when I have a daughter? I feel bad. Doing all this— networking and leaving Ai-chan makes me feel that way.

It’s not about being an artist. We could be having this same conversation in regards to any other occupation all the same— for any number of reasons we become too busy, pulled apart; art isn’t embarrassing, it’s an occupation. And anyway, Ai-chan likes your work, she told me.

Yes but then Ai-chan gets bored of me. She literally says, No not sculpture again! And this is the 3rd Saturday in a row that I don’t take her to gymnastics. Ai-chan is not progressing as she was before...

What would be better, to be busy for some other reason?

I think about those mom’s that do everything for the children, putting them in music lessons, in sports; I feel I am such a self-centered mom sometimes. It feels silly because I am not some big important artist, I just have one piece in this fair and take my whole weekend to come here, to Catskill, spend money to come here, stay overnight, talk about sculpture. These objects are silly. Ai-chan could be learning things, being taken to lessons that maybe she loves or is prodigy and she grows up with a talent far superior to mine... but I will never know because I don’t take her. That is the irony.

Is Ai-chan particularly good at gymnastics?

Not really. But she is tough. She is better at climbing on scaffolding actually. And the forklift.

︎

[...] untalking, wordless shimmers of Yasue’s bone, metal, and stone compositions—the anti-narrative bedrock of her practice, which is a performance of tactility and translating the vision into object. In this way, her sculptures yield a totemic power, evoking the smoke of her, the artist’s intentions. On the other hand, there is no telling what they say. Just like Yasue, they are non-didactic. Who do the sculptures address? Do they speak in first-person, third-person? Or do they simply say, you.

What if I write directly to you? Like a letter.

︎

You. I think I mentioned once this knack I have of hardly recording anything and my tendency to neglect note-taking until later on, trying to remember whatever it was we discussed together. While this has emerged as an integral exercise in our creative approach to dialoguing, it is also painstaking for me to get at the heart of things that left an impression on me, fighting to reprise a memory with some clarity. Even as you create new sculptures and I write these words, we are yielding to a consensual erasure of many things.

Whether to reenact the things we say solely from memory or to rely on the recording device for evidence: I accept both without making a hierarchy amongst them.

But the most important thing is that I know how integral the absence of a recording device is— I mean, for us. Not because the connoisseurs tell me to choose so as to romanticize the artist's perception; we simply and inevitably keep forgetting to record our conversations. And the fact is that, because of this, the most important evidence has been missed, like our natural dialogue, or even a snapshot of us in Catskill. Now I know why I like Western classism. And Bacon.

︎

Can you tell me what “Mass Inception” is about?

“Mass Inception” was referring to mother nature, mood changes during pregnancy, and a more voluminous approach to form. It is an eruption caught in motion, a volcanic limbo between the land and the air. It is also my body as I became a small mountain, a mother.

I built that foundation made of steel armature covered with urethane foam whose shape was curved by literal burning with blow torch and then coating with varnish. This was right before I retired from the studio practice for a while when I realized I was pregnant and I could not go on working with such materials. I walked away— I had Ai-chan. I thought, ah, now is my chance to stop with sculpture. I was so happy to become less competitive, less pressure to make. I was a mother. That was four years ago.

I came back to the piece this year and applied the surface material which is like a faux-earth: terracotta blended with epoxy resin and spread over the surface of the charred foam.

︎

Did you see this piece in your head before you began? Or is its assemblage a reaction to the process of sculpting? While sculpting, are you re-interpreting and reacting to unplanned directions?

I have the vision in mind. I get the visions beforehand. They can change, but I see the piece in my head always.

When do you get visions? Are you always open or do they come under particular circumstances?

I get them frequently, doing mundane things. I don’t need travel or to go foraging for inspiration. Actually I have the clearest ideas just doing my routines— I live over there, I take Ai-chan to school across the street, I go to my studio behind Platz where I find David— I see through this, and in moments of isolation. I have the best visions in the bath.

When you finish a sculpture, is it normally close to what you envisioned?

Depends.

︎

Have you thought about the timing?

Should we have waited to write these things— waited for when artists are typically remembered, when you are old or dead?

You just turned 47. You just spoke to me— you speak to me. You tell me about the cars drifting through the mountain roads in Japan. You saw them racing when you were a teenager. You tell me about driving in New York and seeing the architecture passing in blurs of color and material, fusing with your thoughts of sculpture, thoughts of combining what you have like terra cotta and urethane foam, paper, stone, brass...

︎

The toughness of being my gallerist is not because I make a grotesque aesthetic. The toughness is that the gallerist almost has to treat/handle my work as a dead artist's rather than a living artist’s, i.g. the gallerist has to curate the work across the artist's age or time period of a life. My life.

︎

I’m in your studio again as we turn our attention now to translating Pt. 1 and organize a print edition to accommodate the Tokyo Art Book Fair in October (meanwhile, I am writing this, Pt. 2).

By cc’ing me on every email with the translators, Rumi and Nahoko, I intuited that you want me google-translating every correspondence, observing as you coordinate the rewriting of our article, Sculptural Autopsies with Yasue Maetake Pt. 1, into Japanese. There and again I see you all separating the English into fragments, questioning word choices and double-entendres, slowly equating the language to its Japanese mirror-image.

As my original text became logographic, unintelligible to me, you can now read our article for the first time in your mother tongue and understand with clarity what was previously oblique in English. You describe to me the decisions Rumi and Nahoko made when ascribing certain English words to Japanese characters; how seemingly subtle distinctions in their interpretations influenced how to approximate sentiments from the original English text into Japanese.

To lose understanding of my own article was to look once again at sculpture, or at least at yours, which dictate no narrative and no single language in their exposition— if I snag on them, something liquid and sentimental might escape me, dispensing a thought in its wake, a hard-to-say, fleeting thing that suggests I simply look twice at the shapes you’ve made.

︎

︎

[09/15/2021]Email regarding the word “reaper” and its counterpoint in Japanese:

彼岸" leads to the "boundary" or “barrier” which appears later in the writing. "彼岸" is an unstable "辺獄" while "あの世" is an absolute place, and that which is the antonym to "in this world". Therefore "彼岸" is more oscillant.

Perhaps you might think "辺獄" could also work as a translation. But the character "獄" is too strong and thus, implies hell unnecessarily. Since “Grim Reaper” will appear later, I also want to neutralize the questionable strong connotation of death and hell. Another reason to use “彼岸" is an image of a field and river full of natural light. That is more suitable for my "Ascending Industrial Bouquet," whose translucent body accumulates the light. “彼岸" also means Spring and Autumn equinox, which is my birthday, too.

As for the “大鎌”, I wanted to use the character “刈” which refers more a simple device (a scythe) with a more linear character form, as opposed to “大鎌” which is more arched and compact. The skeletal armature of “Ascending Industrial Bouquets” consists of the linear structure.

︎

See your hands turning the steering wheel of the car, which turns the wheels of the car, which brings you onto Forest Ave and home again. See yourself at home, alive and surprised (because you are a somewhat bad driver, or so says David). See yourself move automatically through the home. See yourself move deliberately through the studio: see yourself assembling, responding to the thoughts of laundry, thoughts of your daughter, welding certain arguments into lobes of resin, into cages of effort, her little knees, barely recovered from a scrape, air barely different than mesh, oil, seashell, wedding veil, hot glue, photos from your life coming through the glue, sculptures interrupting, air on air, thinly, daily, more shape, more memory in the form of a career, in the form of paper, wet pulp drying on metal whose rust leaves striking blue stains.

︎

Working on the translation of “reaper” became the same intensity as my sculpture making, in which I am constantly maintaining the oscillation between the two places where I regard only the essence can exist. I am very happy to come up with the word "彼岸."

At this point, you perhaps understand that Japanese (especially Chinese) is based on the symbolism called logogram. I am living in a hieroglyphic view of the world while Japanese also uses a half phonographic system, like English. Hope this experience helps you understand. But even more so, I simply wanted to share with you this linguistic epiphany and happiness.

︎

As we talk, your life becomes a story we both remember, a memory imparting onto me or a confusion lying in wait... your patience with this portrait as I write this all down, as I try to tell us both about your life.

Follow Yasue:

Web: www.yasuemaetake.com

Instagram: @yasuemaetake

Yasue Maetake:

Yasue Maetake is a Toyko-born artist living and working in New York. Using

a wide variety of influences, her sculpture evokes associations with

Baroque Dynamism and Animism, along with futuristic variations of

natural forms and industrial aesthetics. They partner directly with

human customs and technology.Addison Bale:

is a writer and artist from NYC. His work is viewable online: https://adi-bale.com

More from “Shedding”:

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

EST 2020

︎

© THE QUARTERLESS REVIEW ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

EST 2020

︎

© THE QUARTERLESS REVIEW ALL RIGHTS RESERVED